Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Royal Australian Navy (the Navy) currently has eight ANZAC class frigates. The 2016 Defence White Paper stated that:

The Government is bringing forward the future frigate program to replace the Anzac Class frigates. A continuous build of the Navy’s future frigates will commence in 2020. The future frigates will be built in South Australia following completion of a Competitive Evaluation Process.1

2. On 29 June 2018, the Australian Government announced the outcome of the competitive evaluation process, which had assessed designs by three shipbuilders:

The frigates, to be designed by BAE Systems and built by ASC Shipbuilding, are central to our plan to secure our nation, our naval shipbuilding sovereignty and create Australian jobs.

BAE’s Global Combat Ship – Australia will provide our nation with one of the most advanced anti-submarine warships in the world – a maritime combat capability that will underpin our security for decades to come.

The Future Frigates, named the Hunter class, will be built in Australia, by Australians, using Australian steel.

This $35 billion program will create 4,000 Australian jobs right around the country and create unprecedented local and global opportunities for businesses large and small.

The Hunter class will begin entering service in the late 2020s replacing the eight Anzac Frigates, which have been in service since 1996.2

3. Construction of the Hunter class frigates is part of the Australian Government’s continuous naval shipbuilding program intended to develop sovereign Australian shipbuilding and sustainment. The Australian Government’s 2020 Force Structure Plan publicly reported that the cost of the Hunter class frigates was $45.6 billion out-turned.3

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The acquisition of nine Hunter class frigates is a key part of the Australian Government’s substantial planned expenditure on naval shipbuilding and maritime capability4 and contributes to the ongoing capability of the Australian Defence Force.5 This audit examined the effectiveness of the Department of Defence’s (Defence) procurement of Hunter class frigates to date and the achievement of value for money through Defence’s procurement activities.

5. The audit builds on previous Auditor-General work on Defence’s acquisition and sustainment of Navy ships and implementation of the Australian Government’s 2017 Naval Shipbuilding Plan, to provide independent assurance to the Parliament on Defence’s planning, procurement, decision-making and advising, contracting and delivery of the Hunter class frigates to date.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Defence’s procurement of Hunter class frigates and the achievement of value for money to date.

7. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Did Defence conduct an effective tender process?

- Did Defence effectively advise government?

- Did Defence establish fit-for-purpose contracting arrangements?

- Has Defence established effective contract monitoring and reporting arrangements?

- Has Defence’s expenditure to date been effective in delivering on project milestones?

8. This audit reports on Defence procurement activity and developments in project SEA 5000 Phase 1 (Hunter class frigate design and construction) to March 2023. The government and Defence have indicated that the planned Hunter class capability has been considered as part of the Defence Strategic Review and related government processes.6

Conclusion

9. The Department of Defence’s management to date of its procurement of Hunter class frigates has been partly effective. Defence’s procurement process and related advisory processes lacked a value for money focus, and key records, including the rationale for the procurement approach, were not retained. Contract expenditure to date has not been effective in delivering on project milestones, and the project is experiencing an 18-month delay and additional costs due in large part to design immaturity.

10. Defence did not conduct an effective limited tender process for the ship design. The value for money of the three competing designs was not assessed by officials, as the Tender Evaluation Plan (TEP) proposed that government would do so. The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) and the Defence Procurement Policy Manual required officials responsible for procurement to be satisfied, after reasonable inquiries, that the procurement achieved a value for money outcome. Defence did not otherwise document the rationale for the TEP not requiring a value for money assessment or comparative evaluation of the tenders by officials.

11. Defence’s advice to the Australian Government at first and second pass was partly effective. While the advice was timely and informative, Defence’s advice at second pass was not complete. Defence did not advise that a value for money assessment had not been conducted by Defence officials and that under the TEP Defence expected government to consider the value for money of the tenders.

12. Defence has established largely fit-for-purpose contracting arrangements for the design and productionisation stage, and largely effective contract monitoring and reporting arrangements to ensure adequate visibility of performance and emerging risks and issues. However, the contract management plan was established 44 months (3.6 years) after contract execution.

13. Defence’s expenditure to date has not been effective in delivering on project milestones, and the cost of the head contract has increased. Lack of design maturity has resulted in an 18-month delay to the project and extension of the design and productionisation phase, at an additional cost to Defence of $422.8 million.7 At January 2023 the project was forecast to exceed the whole of project budget approved by government by a significant amount.

Supporting findings

Tender process

14. To select ship designs for the government-approved competitive evaluation process (CEP) — a limited tender approach — Defence conducted a shortlisting process informed by its own assessments and analysis by the RAND Corporation. Defence did not retain complete records of its assessments, and its rationale for shortlisting all selected designs for the CEP was not transparent. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.20 )

15. Defence’s Endorsement to Proceed documentation for the CEP approved the Request for Tender (RFT) going ahead and set out tender evaluation criteria and expectations for the assessment of value for money. However, the expectations regarding the assessment of value for money were not operationalised, as the Tender Evaluation Plan (TEP) specified that value for money would not be assessed by Defence. (See paragraphs 2.21 to 2.29)

16. The TEP, which was approved by the probity advisor, did not document how the evaluation process would address the core rule of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), which is achieving value for money. The CPRs require officials responsible for procurement to be satisfied, after reasonable inquiries, that the procurement achieves a value for money outcome. Defence did not document the rationale for the TEP not requiring a value for money assessment or comparative evaluation of the tenders by officials. (See paragraphs 2.30 to 2.35)

17. As the tender evaluation process was underpinned by a TEP that specifically excluded a value for money assessment of tenders by officials, the Source Evaluation Report (SER) did not include a value for money assessment. (See paragraphs 2.36 to 2.39)

18. Defence conducted the tender evaluation in accordance with the TEP but did not retain a record of delegate approval of the SER Supplement document, which recorded the outcomes of the evaluation process. (See paragraphs 2.40 to 2.45)

19. Not all probity matters were recorded and addressed as required by the November 2016 Legal Process and Probity Plan for the procurement. (See paragraphs 2.46 to 2.51)

Advice to government

20. Defence’s advice to government at first pass was timely and informative. However, its recommendation to include the BAE Type 26 design in the competitive evaluation process (CEP) as the third option, instead of the alternate, was not underpinned by a documented rationale. (See paragraphs 2.53 to 2.56 )

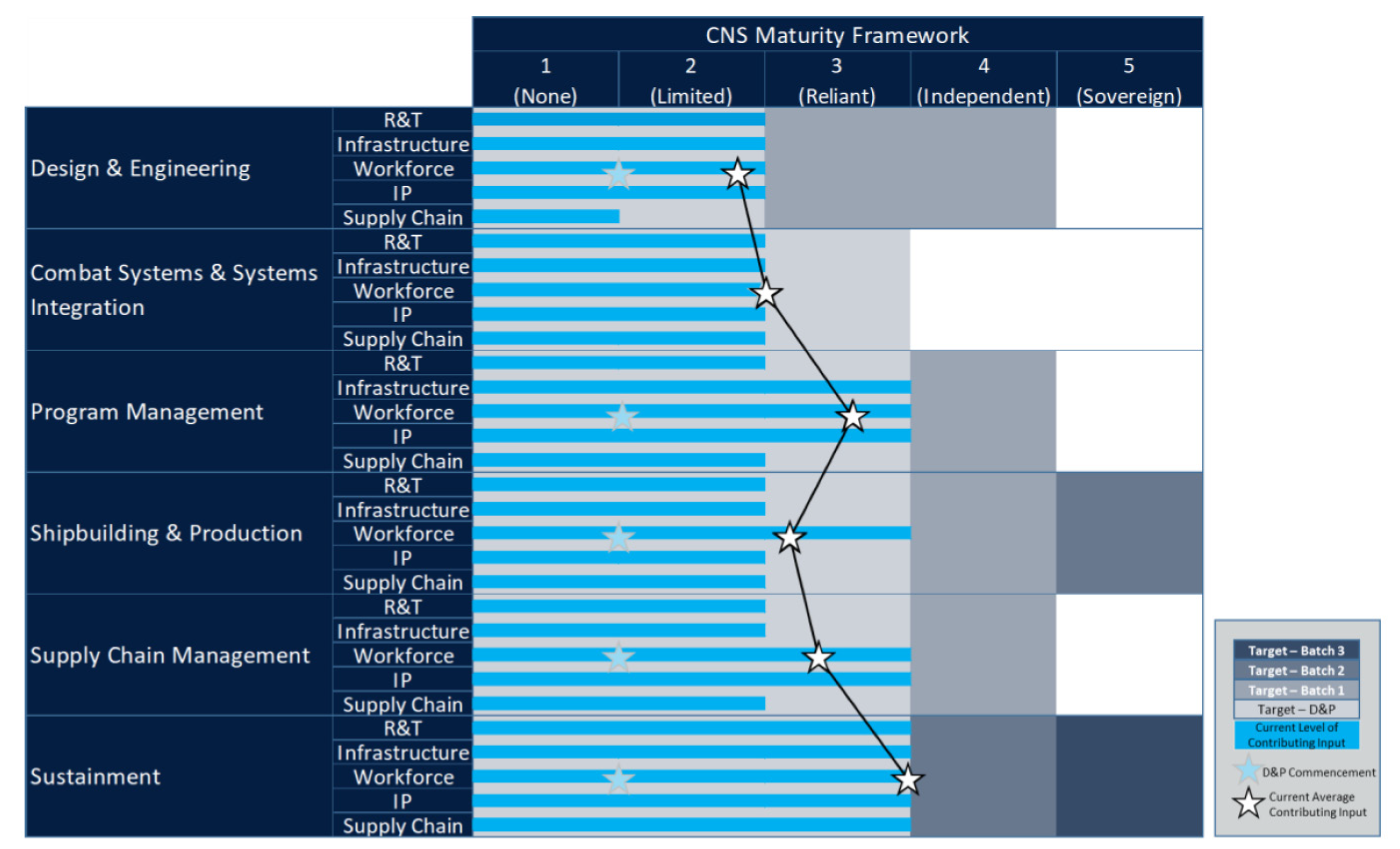

21. At second pass, Defence’s advice to government on the selection of the preferred ship design was not complete. Defence did not draw the following matters to government’s attention.

- Contrary to the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), a value for money assessment had not been conducted by Defence officials. Defence’s assessment was against the high-level capability requirements.

- Under the Tender Evaluation Plan (TEP) Defence expected government to consider the value for money of the tenders.

- A 10 per cent reduction to tendered build costs had been applied by Defence. The reduction had not been negotiated with tenderers.

- Sustainment cost estimates had not been prepared for government consideration as required by the Budget Process Operational Rules applying to Defence. (See paragraphs 2.57 to 2.85 )

22. In its assessment, which was included in Defence’s second pass advice to government, the Department of Finance (Finance) drew attention to the 10 per cent reduction to tendered build costs and other limitations in Defence’s advice on costs. Finance did not comment on Defence’s lack of a value for money assessment, compliance with the CPRs or quality of advice regarding value for money. (See paragraphs 2.79 to 2.80)

Contracting arrangements

23. When it was executed in December 2018, the head contract reflected the contract negotiation outcomes reported to the delegate. However, the extent to which these outcomes were in line with Defence’s original negotiation positions is not transparent because not all outcomes were clearly defined or reported against, and some negotiation issues were not finalised when the head contract was signed. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.12)

24. Milestones under the head contract have clear entry and exit criteria and due dates, with the first milestone payable on contract execution. (See paragraph 3.15)

25. Performance expectations are clearly set out in the contracted statement of work and are linked to performance measures, with processes to manage poor performance included in the conditions of contract. Commercial levers to incentivise the prime contractor (BAE Systems Maritime Australia) and drive value for money outcomes in project delivery are limited. Key commercial levers such as profit moderation provisions were not active at the time the head contract was executed. On 29 June 2022 Defence signed a contract change proposal activating profit moderation for the Scope Fee from 1 July 2022, enlivening a key commercial lever in the head contract. (See paragraphs 3.18 to 3.28)

26. The head contract established processes for managing contract change proposals (CCPs). As of 31 March 2023, there were 93 contract changes and the number of key milestones had increased from 25 to 37. Thirty-six of the 93 CCPs approved by Defence were price impacting and the cost of the contract has increased by $693.2 million. This represents a 36 per cent increase to the design and productionisation cost of the Hunter class. (See paragraphs 3.13 to 3.17 )

27. Amendments to the head contract mean that between December 2018 (contract execution) and March 2023, the contract has increased in price from $1,904.1 million (GST exclusive) to $2,597.4 million (GST exclusive). The contract price remained within the (PGPA Act) section 23 commitment approval amount as of 31 March 2023. (See paragraphs 3.13 to 3.17 )

Monitoring and reporting arrangements

28. The contract management plan was established 44 months (3.6 years) after execution of the head contract. Defence has managed the contract largely in the absence of an approved contract management plan, and BAE Systems Maritime Australia’s (BAESMA’s) contract master schedule remained unapproved as of March 2023. (See paragraphs 3.29 to 3.30)

29. Contracted requirements for BAESMA to report and meet with Defence have been established. Additional reporting requirements have been established in response to delays in the delivery of a contractable offer for the batch one build scope from BAESMA. (See paragraphs 3.38 to 3.43)

30. Governance and oversight arrangements — to manage and oversee project performance, risks and issues — have generally been established in a timely manner. Defence records indicate that governance bodies have met at the expected cadence and with the required Defence senior leadership attendance. (See paragraphs 3.32 to 3.37 and 3.44 to 3.45 )

31. Defence has established appropriate project and program monitoring arrangements. These include performance monitoring mechanisms to inform Defence of relevant developments overseas, and Independent Assurance Review (IAR) processes. IARs have found insufficient resources, in particular skills and expertise in the project team, and that increased senior leadership attention was needed to manage realised risks and mitigate risks exceeding project risk appetite. (See paragraphs 3.46 to 3.50)

32. More generally, the Surface Ships Advisory Committee (SSAC) was asked to review cost, schedule and risk across the project and provide input to the Australian Government’s Defence Strategic Review. Defence advised the Parliament in February 2023 that the SSAC’s review had not resulted in any changes in scope to the project. (See paragraph 3.51)

Delivery on project milestones

33. Actual project expenditure at 31 January 2022 was $2,225.9 million, with $1,308.4 million spent on the head contract with BAE Systems Maritime Australia (BAESMA). Defence has made milestone payments without all exit criteria being met and extended milestone due dates in response to project delays. (See paragraphs 3.53 to 3.84)

34. In June 2021 the Australian Government agreed to extend the design and productionisation period, and to an 18-month delay to the cut steel date for ship one, to enable Defence and BAESMA to improve design maturity and develop a contractable offer for the first batch of ships. The June 2022 contract change proposal to extend the design and productionisation phase increased the contract price by $422.8 million (GST exclusive). (See paragraphs 3.106 to 3.116)

35. Design immaturity has affected Defence’s planning for the construction phase, led to an extension of the design and productionisation phase at additional cost to Defence, and diverted approved government funding for long lead time items to pay for the extension and other remediation activities. Planning for the transition from the existing ANZAC class frigates to the Hunter class capability has also been affected. (See paragraphs 3.104 to 3.126)

36. In December 2021 Defence advised the Australian Government that it considered that BAESMA would recover the schedule delay over the life of the project and deliver the final ship as planned in 2044. (See paragraph 3.108 )

37. The January 2023 Surface Ships Advisory Committee (SSAC) report noted that BAESMA had advised that a risk adjusted schedule would add 16 months to the delivery of the first Hunter class, moving delivery from early 2031 to mid–2032. (See paragraph 3.117)

38. As of January 2023, Defence’s internal estimate of total acquisition costs, for the project as a whole, was that it was likely to be significantly higher than the $44.3 billion advised to government at second pass in June 2018. The SSAC considered that current efforts by Defence and industry were unlikely to result in a cost model within the approved budget. As of March 2023, while Defence had advised portfolio Ministers that the program is under extreme cost pressure, it had not advised government of its revised acquisition cost estimate, on the basis that it is still refining and validating the estimate. (See paragraphs 3.86 to 3.97)

39. Defence has approved BAESMA’s Continuous Naval Shipbuilding and Australian Industry Capability (AIC) strategies and plans, with an Australian contract expenditure target of 58 per cent of total contract value and 54 per cent of the design and productionisation phase. (See paragraphs 3.127 to 3.135)

40. The February 2022 Independent Assurance Review (IAR) was not assured that there was a clear path to realising the policy objective of a local surface combatant ship designing capability, due to delays in transferring relevant personnel and skills to Australia. (See paragraph 3.137)

41. In early 2023 the project remained in the design and productionisation phase, which is intended to inform Defence’s planning and contracting for the ship build, including Defence’s final estimate of construction costs. Defence advised the Parliament in February 2023 that the project is managing a range of complex risks and issues and is considering remediation options. Defence further advised that the Hunter class was one of the capabilities that were reviewed by government in the context of the Defence Strategic Review, which presented its final report to ministers on 14 February 2023. A public version of the final report was released on 24 April 2023. (See paragraphs 3.142 to 3.145)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.13

The Department of Defence ensure compliance with the Defence Records Management Policy and statutory record keeping requirements over the life of the Hunter class frigates project, including capturing the rationale for key decisions, maintaining records, and ensuring that records remain accessible over time.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.101

The Department of Defence ensure that its procurement advice to the Australian Government on major capital acquisition projects documents the basis and rationale for proposed selection decisions, including information on the department’s whole-of-life cost estimates and assessment of value for money.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

42. The summary responses from the Department of Defence, with ANAO comments, and the Department of Finance are provided below. Their full responses are included at Appendix 1.

Department of Defence

The Hunter class frigate program is a multi-stage procurement that will span three decades with an approval pathway that returns to Government multiple times. In June 2018 Government second pass approval was sought for the selection of the Type 26 as the reference ship design; the sale of ASC Shipbuilding; $6.7 billion in funding for the design and productionisation phase; and agreement to return progressively for funding for the construction of the ships in three batches. Approval has not been sought for the funding to acquire nine Hunter class frigates.

Defence is committed to complying with statutory record keeping requirements. Defence notes that the Hunter class frigate project has over 730,000 documents (more if the multiple versions of documents as they are amended over time are included) within its Records Management System. Of the thousands of documents identified and requested by the ANAO, less than ten documents were unable to be located across the Department.

Defence ensures all procurement advice to Government on major acquisition projects includes the basis and rationale for proposed decisions, including value for money and whole-of-life cost estimates, and contends that this did occur in relation to the Hunter class frigate project.

ANAO comments on Department of Defence summary response

43. As discussed in this audit report in paragraphs 2.7 to 2.15, shortcomings in Defence record-keeping are discussed throughout the report. In the context of the competitive evaluation process, Defence did not retain complete records of the key decisions made during the shortlisting process for the evaluation activity, including: the basis for the Ship Building Steering Group’s decision to approve seven ship designs for further analysis; and the rationale for the Defence Secretary’s (the decision maker’s) selection of the BAE Type 26 over the French FREMM (DCNS) as the third option. In the context of Defence’s development of advice for second pass government approval, the minutes of the relevant Defence Committee meeting were not retained and it is unclear what deliberations took place. The hand-written notes provided to the ANAO as evidence did not include references to the relative value for money of the tenders (discussed in paragraphs 2.64 to 2.66).

44. As discussed in this audit report in paragraphs 2.53 to 2.102, Defence’s advice to the Australian Government at second pass on the selection of the preferred ship design did not include an assessment of value for money or include whole-of-life cost estimates as required by the Budget Process Operational Rules applying to Defence.

Department of Finance

In relation to the procurement process conducted by Defence, a key Finance role is to issue and support the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) which set out the rules that officials must comply with when undertaking procurement. It is the responsibility of the Accountable Authority to provide a framework and instructions to relevant entity officials to enable them to carry out procurement processes in a manner that is compliant with the CPRs. The CPRs do not include a requirement to consult Finance on compliance with the CPRs. However, Finance maintains and promotes a CPRs advisory function that entities can consult when undertaking procurements.

In formulating its advice to Government, Finance drew on information provided by Defence throughout the procurement process and in the lead up to the Government decision. This provided Finance with visibility of Defence’s assessment of a number of matters (including quality of the goods to be acquired, how well the goods would meet their intended purpose, relevant experience and performance history of potential suppliers and whole-of-life costs) that went to the consideration of value for money. Finance highlighted these Defence considerations in advice to Government.

45. At Appendix 2, there is a summary of improvements that were observed by the ANAO during the audit.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Procurement

Contract Management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Royal Australian Navy (the Navy) currently has eight ANZAC class frigates. The ANZAC class is a long-range frigate capable of air defence, surface and undersea warfare, surveillance, reconnaissance and interdiction. The first of class ship, HMAS ANZAC, was commissioned in 1996. The 2009 Defence White Paper announced that:

The Government will also acquire a fleet of eight new Future Frigates, which will be larger than the Anzac class vessels. The Future Frigate will be designed and equipped with a strong emphasis on submarine detection and response operations. They will be equipped with an integrated sonar suite that includes a long-range active towed-array sonar, and be able to embark a combination of naval combat helicopters and maritime Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV).8

1.2 The 2016 Defence White Paper stated that:

The Government is bringing forward the future frigate program to replace the Anzac Class frigates. A continuous build of the Navy’s future frigates will commence in 2020. The future frigates will be built in South Australia following completion of a Competitive Evaluation Process.9

1.3 On 29 June 2018, the Australian Government announced the outcome of the competitive evaluation process:

The frigates, to be designed by BAE Systems and built by ASC Shipbuilding, are central to our plan to secure our nation, our naval shipbuilding sovereignty and create Australian jobs.

BAE’s Global Combat Ship – Australia will provide our nation with one of the most advanced anti-submarine warships in the world – a maritime combat capability that will underpin our security for decades to come.

The Future Frigates, named the Hunter class, will be built in Australia, by Australians, using Australian steel.

This $35 billion program will create 4,000 Australian jobs right around the country and create unprecedented local and global opportunities for businesses large and small.

The Hunter class will begin entering service in the late 2020s replacing the eight Anzac Frigates, which have been in service since 1996.10

1.4 Construction of the Hunter class frigates is part of the Australian Government’s continuous naval shipbuilding program intended to develop sovereign Australian shipbuilding and sustainment. The Australian Government’s 2020 Force Structure Plan publicly reported that the cost of the Hunter class frigates was $45.6 billion out-turned.11

SEA 5000 Phase 1 – Hunter class frigates design and construction

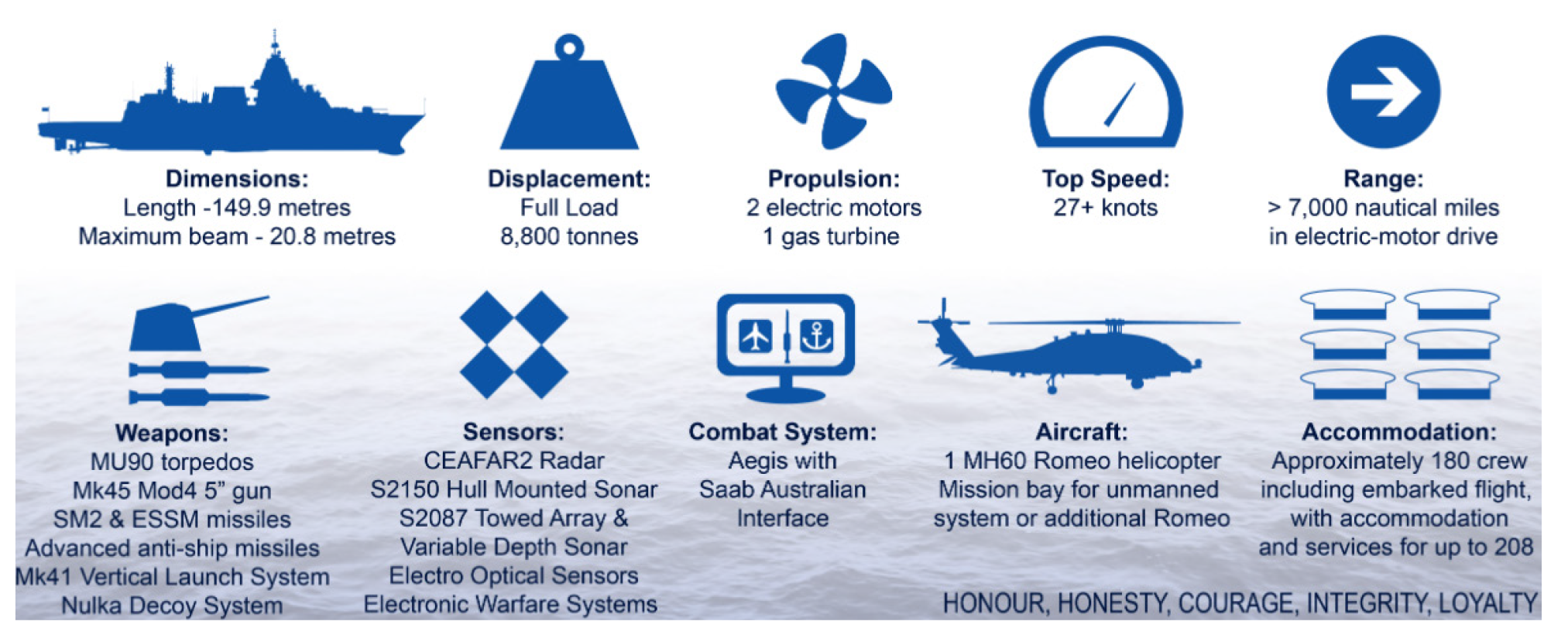

1.5 Nine Hunter class frigates, based on BAE Systems’ Type 26 Global Combat Ship design with Australian modifications, are to be acquired under Phase 1 of the Hunter class frigate program (SEA 5000).12 Project SEA 5000 Phase 1 (the project) is focused on design, construction and delivery of the Hunter class mission and support systems. An image of the planned Hunter class frigate is at Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Image of the planned Hunter class frigate

Source: Image of the planned Hunter class frigate provided by Defence.

1.6 The project is to be delivered in the following five stages:

- competitive evaluation process to identify a designer and builder — completed in 2018 (discussed in chapter two of this audit report);

- design and productionisation — in progress (discussed in chapter three of this audit report);

- batch one build (ships 1–3) (planned to be considered and contracted to follow the design and productionisation stage);

- batch two build (ships 4–6) (planned to be considered and contracted to follow the construction of batch one); and

- batch three build (ships 7–9) (planned to be considered and contracted to follow the construction of batch two).13

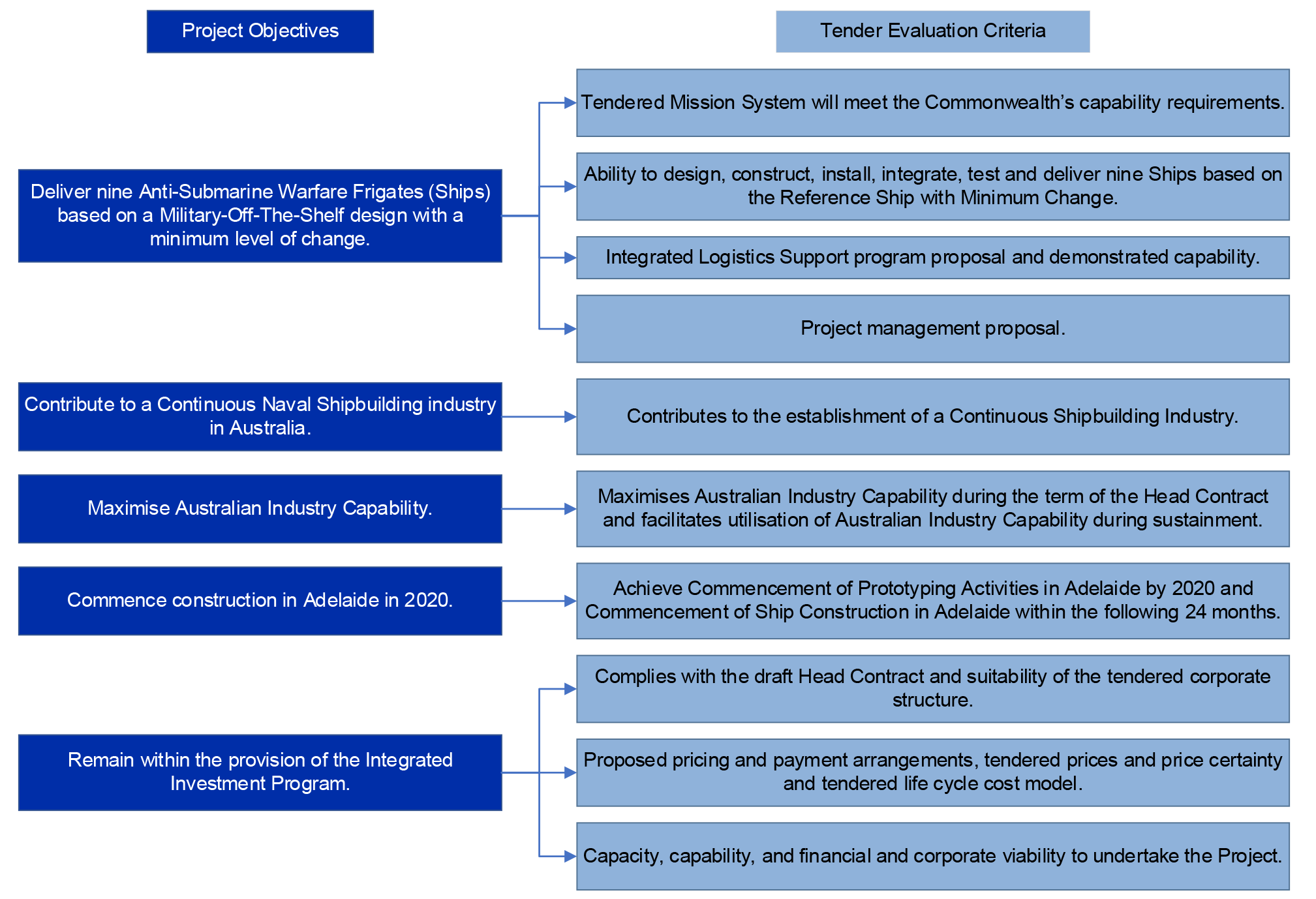

1.7 The platform characteristics and primary systems of the approved Hunter class design are summarised in Figure 1.2. Key modifications to BAE System’s Type 26 Global Combat Ship (known as the reference ship design), to meet Australian requirements, include the integration of the United States Navy’s Aegis combat management system (CMS) with a Saab Australian interface and Australian CEA Technologies phased array radar.14

Figure 1.2: Platform characteristics and primary systems of the Hunter class frigates

Source: Defence.

Project management arrangements

1.8 The Chief of Navy is the capability manager, and the Navy is the capability owner.15 Within the Navy, the Director-General Surface Combatants and Aviation (the Program Sponsor) is responsible for ensuring that the outcomes of all program activities are achieved and that these outcomes remain aligned with Defence strategic objectives. Within the Surface Combatants and Aviation Branch, the Director Frigates (the Capability Project Sponsor) sets direction for the project and ensures that activities and outputs are consistent with the capability needs and priorities of the capability user.

1.9 Defence’s Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment Group is responsible for managing the SEA 5000 Phase 1 acquisition on behalf of the Navy.16 Within the Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment Group, the Director-General Hunter Class Frigates (the overall Program Manager) is accountable for delivery of the mission and support systems. The Director-General Hunter Class Frigates is supported by the Director-General Maritime Integrated Warfare Systems, who is responsible for the combat system. The Hunter class project is managed by the Hunter Class Frigates Branch which is part of the Major Surface Combatants and Combat Systems Division. The project is managed day-to-day by the project team and Project Director based in Canberra with onsite project management provided by the Naval Construction Branch based at the Osborne shipyard in South Australia.

Head contract

1.10 On 14 December 2018, Defence entered into a head contract with ASC Shipbuilding (a subsidiary of BAE Systems Australia) valued at $1,904.1 million, covering the design and productionisation work to support the build of the Hunter class frigates As discussed in paragraphs 1.13 to 1.15, ASC Shipbuilding commenced trading as BAE Systems Maritime Australia (BAESMA) on 11 December 2020.

1.11 As at 31 March 2023, the value of the head contract had increased to $2,597.4 million. The key components of the head contract price as at 31 March 2023 are outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Components of the head contract price at 31 March 2023 ($AUD equivalent)

| Price component |

Total component price ($AUD) |

| Management servicesa |

658,794,949 |

| Design and productionisationa |

1,323,459,685 |

| Long lead time itemsb |

245,971,931 |

| Pass throughc |

369,148,790 |

| Total |

2,597,375,355 |

Note a: The management services and design and productionisation component prices include amounts for management reserve, uncertainty and other adjustments, as well as scope fee comprising BAE Systems Maritime Australia’s profit margin (see paragraphs 3.21 to 3.23).

Note b: Long lead time items are defined under the head contract as: ‘a Mission System component or Support System Component that: a) the Contractor commits to procure as part of a Scope which will be delivered to the Commonwealth as part of another Scope; and b) is necessary to ensure timely delivery of the Supplies in accordance with the Approved CMS [Contract Master Schedule]’.

Note c: The ‘pass through’ component of the contract price comprises funding for expenses incurred by BAE Systems Maritime Australia in performing the work under the contract on a cost recovery basis for which no fee is to apply, in accordance with allowable cost rules. Examples include securities; warranties; intellectual property licence fees and royalties; insurances; travel and relocation costs; government fees and charges; and shipyard and Commonwealth premises costs including lease or licence fees, and utilities.

Note: Column and row totals may not add up due to rounding of individual figures.

Source: Defence documentation.

1.12 The head contract established between the Commonwealth and BAESMA sets out terms to govern the long-term relationship and contains specific provisions for management services and the design and productionisation scope of the project. Defence plans to return to the Australian Government for approval for subsequent scopes to be added under the head contract, starting with the batch one build (ships 1–3).

ASC Shipbuilding (later BAESMA)

1.13 As part of the procurement process and prior to execution of the head contract, the Commonwealth transferred ASC Shipbuilding to BAE Systems Australia at a nominal cost of $1.00 on 14 December 2018. The Commonwealth subsequently entered into the head contract for the Hunter class frigate program with ASC Shipbuilding. On 29 June 2018, the same day as the outcome of the competitive evaluation process was announced, the Australian Government announced the transfer of ASC Shipbuilding:

ASC Shipbuilding, currently wholly owned by the Commonwealth, will become a subsidiary of BAE Systems during the build. This ensures BAE Systems is fully responsible and accountable for the delivery of the frigates and ensures the work will be carried out by Australian workers and create Australian jobs.

The Commonwealth of Australia will retain a sovereign share in ASC Shipbuilding while BAE manages the program. At the end of the program the Commonwealth will resume complete ownership of ASC Shipbuilding, thereby ensuring the retention in Australia of intellectual property, a highly skilled workforce and the associated equipment.

By the conclusion of the frigate build, ASC Shipbuilding will be a strategic national asset capable of independently designing, developing and leading the construction of complex, large naval warships.17

1.14 The transaction formed part of a broader restructure of ASC Pty Ltd, a Government Business Enterprise18, under which ASC Shipbuilding, including workforce engaged on the Air Warfare Destroyer and Offshore Patrol Vessel projects, were transferred to BAE Systems Australia.

1.15 ASC Shipbuilding commenced trading as BAE Systems Maritime Australia (BAESMA) on 11 December 2020.

Strategic relationship

1.16 The head contract between the Commonwealth and BAESMA commits the two parties to work to develop a strategic relationship in accordance with a set of principles (the principles and corresponding performance measures are discussed at paragraphs 3.18 to 3.20 of this audit report).19 The parties have agreed to ‘work together in a cooperative and collaborative manner to achieve the contract objectives’, including by ‘developing a culture of open communication and transparency’ and ‘discussing all issues in an open and honest manner’. As discussed at paragraph 3.40, Defence established a Team Hunter Enterprise Plan to give effect to these principles, comprising of 24 initiatives to be implemented by the end of 2022.

Project funding and expenditure

1.17 Actual project expenditure at 31 January 2023 was $2,225.9 million, with $1,308.4 million spent on the head contract with BAESMA. The allocated funding and actual expenditure as at 31 January 2023 on the Hunter class program and associated project costs are outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Allocated funding and actual expenditure at 31 January 2023 ($AUD)

| Funding source |

Allocated funding incl. contingency (PBS 2022–23 $AUD) |

Contingency funding (PBS 2022–23 $AUD) |

Expended to 31 January 2023 ($AUD) |

Difference ($AUD) |

| SEA 5000 Phase 1 project allocation |

6,137,553,884 |

597,867,126 |

2,225,929,493 |

3,911,624,391 |

| Other project cost allocation |

1,020,353,262 |

66,271,341 |

378,981,046 |

641,372,216 |

| Total |

7,157,907,146 |

664,138,467 |

2,604,910,539 |

4,552,996,607 |

Note: Column and row totals may not add up due to rounding of individual figures.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

Previous Auditor-General reports

1.18 Since 2016–17, the Auditor-General has tabled seven performance audit reports relating to naval procurement, maritime sustainment and related matters.

- Auditor-General Report No. 48 2016–17 Future Submarine — Competitive Evaluation Process.

- Auditor-General Report No. 39 2017–18 Naval Construction Programs — Mobilisation.

- Auditor-General Report No. 30 2018–19 Anzac Class Frigates — Sustainment.

- Auditor-General Report No. 22 2019–20 Future Submarine — Transition to Design.20

- Auditor-General Report No. 12 2020–21 Defence’s Procurement of Offshore Patrol Vessels — SEA 1180 Phase 1.

- Auditor-General Report No. 15 2021–22 Department of Defence’s Procurement of Six Evolved Cape Class Patrol Boats.

- Auditor-General Report No. 7 2022–23 Defence’s Administration of the Integrated Investment Program.21

1.19 The Auditor-General has made recommendations to Defence on retaining evidence and advice regarding decision-making in procurement. Key messages from these reports included maintaining adequate records when undertaking complex negotiations and having effective oversight to realise value for money under a contract.

1.20 Project SEA 5000 Phase 1 (Hunter class frigates) has also been included in the annual Defence Major Projects Report (MPR) since 2019–20.

- Auditor-General Report No. 19 2020–21 2019–20 Major Projects Report, pp. 151–58.

- Auditor-General Report No. 13 2021–22 2020–21 Major Projects Report, p. 115 and pp. 135–42.

- Auditor-General Report No. 12 2022–23 2021–22 Major Projects Report, p. 116 and pp. 137–45. This is the most recent MPR, presented to the Parliament on 9 February 2023.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.21 The acquisition of nine Hunter class frigates is a key part of the Australian Government’s substantial planned expenditure on naval shipbuilding and maritime capability22 and contributes to the ongoing capability of the Australian Defence Force.23 This audit examined the effectiveness of the Department of Defence’s (Defence) procurement of Hunter class frigates to date and the achievement of value for money through Defence’s procurement activities.

1.22 The audit builds on previous Auditor-General work on Defence’s acquisition and sustainment of Navy ships and implementation of the Australian Government’s 2017 Naval Shipbuilding Plan, to provide independent assurance to the Parliament on Defence’s planning, procurement, decision-making and advising, contracting and delivery of the Hunter class frigates to date.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.23 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Defence’s procurement of Hunter class frigates and the achievement of value for money to date.

1.24 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Did Defence conduct an effective tender process?

- Did Defence effectively advise government?

- Did Defence establish fit-for-purpose contracting arrangements?

- Has Defence established effective contract monitoring and reporting arrangements?

- Has Defence’s expenditure to date been effective in delivering on project milestones?

1.25 The audit focused on Defence’s procurement process for the design and productionisation of the Hunter class frigates (SEA 5000 Phase 1) including the rationale for shortlisting decision-making, the tender assessment process, the evidence base for advice to the Australian Government and the execution of contract-based project management and reporting mechanisms. At the time of the audit, the head contract had been signed. Contracts for the building of frigates had not been established.

1.26 The audit did not examine related procurements associated with SEA 5000 Phase 1 including the selection of the combat management system24, the acquisition of government furnished equipment25, the development of naval shipbuilding infrastructure and facilities, or the ASC restructure.

1.27 This audit reports on Defence procurement activity and developments in project SEA 5000 Phase 1 (Hunter class frigate design and construction) to March 2023. The government and Defence have indicated that the planned Hunter class capability has been considered as part of the Defence Strategic Review and related government processes.26 Defence advised the ANAO in April 2023 that:

As at 20 March 2023 there have been no material changes to the Hunter Class Frigate project as a result of the Defence Strategic Review, or other Defence or Government decisions.

Audit methodology

1.28 The audit procedures included:

- reviewing Defence records, including procurement planning, tender assessments, advice, and contract management documentation;

- discussions with Defence officials and Defence contractors;

- walkthroughs of Defence systems; and

- discussions with Department of Finance officials.

1.29 The audit was open to contributions from the public. The ANAO received and considered two submissions.

1.30 The ANAO conducted fieldwork at Defence offices in Canberra, the Osborne shipyard in South Australia, the Henderson shipyard in Western Australia and Fleet Base West in Western Australia.

1.31 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $854,701.

1.32 The team members for this audit were Mark Rodrigues, James Woodward, David Willis, Helen Sellers, Emily Hill, Jude Lynch, Corne Labuschagne, Danielle Page, Sally Ramsey and Amy Willmott.

2. Procurement and decision-making

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Defence’s (Defence) procurement and decision-making processes for the selection of the Hunter class frigate design were supported by an effective tender process and effective advice to the Australian Government.

Conclusion

Defence did not conduct an effective limited tender process for the ship design. The value for money of the three competing designs was not assessed by officials, as the Tender Evaluation Plan (TEP) proposed that government would do so. The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) and the Defence Procurement Policy Manual required officials responsible for procurement to be satisfied, after reasonable inquiries, that the procurement achieved a value for money outcome. Defence did not otherwise document the rationale for the TEP not requiring a value for money assessment or comparative evaluation of the tenders by officials.

Defence’s advice to the Australian Government at first and second pass was partly effective. While the advice was timely and informative, Defence’s advice at second pass was not complete. Defence did not advise that a value for money assessment had not been conducted by Defence officials and that under the TEP Defence expected government to consider the value for money of the tenders.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving Defence’s future record keeping and advice in the procurement context. The ANAO also identified two opportunities for improvement relating to probity management in procurement.

2.1 When undertaking procurement activities, an entity’s accountable authority has a duty to promote the proper (efficient, effective, economical and ethical) use and management of public resources in accordance with the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and to comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs).27 An effective procurement and decision-making process is demonstrated by:

- a value for money focus;

- following approved processes, including those in the approved procurement plan;

- maintaining appropriate records, which underpin the accountability and transparency of procurement and decision-making processes; and

- providing decision-makers with advice that is clear, accurate, complete and timely.

Did Defence conduct an effective tender process?

To select ship designs for the government-approved competitive evaluation process (CEP) — a limited tender approach — Defence conducted a shortlisting process informed by its own assessments and analysis by the RAND Corporation. Defence did not retain complete records of its assessments, and its rationale for shortlisting all selected designs for the CEP was not transparent.

Defence’s Endorsement to Proceed documentation for the CEP approved the Request for Tender (RFT) going ahead and set out tender evaluation criteria and expectations for the assessment of value for money. However, the expectations regarding the assessment of value for money were not operationalised, as the Tender Evaluation Plan (TEP) specified that value for money would not be assessed by Defence.

The TEP, which was approved by the probity advisor, did not document how the evaluation process would address the core rule of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), which is achieving value for money. The CPRs require officials responsible for procurement to be satisfied, after reasonable inquiries, that the procurement achieves a value for money outcome. Defence did not document the rationale for the TEP not requiring a value for money assessment or comparative evaluation of the tenders by officials.

As the tender evaluation process was underpinned by a TEP that specifically excluded a value for money assessment of tenders by officials, the Source Evaluation Report (SER) did not include a value for money assessment.

Defence conducted the tender evaluation in accordance with the TEP but did not retain a record of delegate approval of the SER Supplement document, which recorded the outcomes of the evaluation process.

Not all probity matters were recorded and addressed as required by the November 2016 Legal Process and Probity Plan for the procurement.

2.2 On 4 August 2015, the Prime Minister and the Minister for Defence announced that the Australian Government was:

Bringing forward the Future Frigate programme (SEA 5000) to replace the ANZAC class frigates. As part of this decision, we will confirm a continuous onshore build programme to commence in 2020 – three years earlier than scheduled under Labor’s Defence Capability Plan. This decision will save over 500 hundred jobs and help reduce the risks associated with a ‘cold start’. The Future Frigates will be built in South Australia based on a Competitive Evaluation Process, which will begin in October 2015.28

Assessment and shortlisting process

2.3 The Department of Defence (Defence) conducted an iterative process to assess and shortlist ship designs whose designers would be invited to participate in the competitive evaluation process.29 The shortlisting process that followed the government’s August 2015 announcement involved the following steps.

- An initial market survey and analysis by the RAND Corporation (RAND)30 to identify potentially relevant ship designs. RAND was tasked with examining only military-off-the-shelf design options, with the contracted statement of work excluding new, or clean sheet, designs.

- Consideration of the identified designs by the Defence Ship Building Steering Group31 (chaired by the Chief of Navy) in September 2015.

- Agreement by the government in November 2015 (‘interim pass’) to progress analysis of the initial group of designs that had been identified.32

2.4 In November 2015, the government agreed to the ‘essential criteria’ to be used to further shortlist down to the final three preferred designs. The essential criteria were that the ships33:

- be buildable in Australia within program budget and starting in 2020;

- meet Navy’s capability requirements;

- be able to accommodate communications and combat management systems compatible with Navy’s surface fleet, and comply with applicable Australian legislative and regulatory requirements;

- be based on a steel hull; and

- be supportable in Australia for operation and sustainment.

2.5 Following further shortlisting assessments by RAND34 and Defence, the project sponsor (the Chief of Navy) presented a paper on the future frigate design options to the February 2016 meeting of the Defence Capability and Investment Committee.35 The paper advised that Defence’s assessment was that four of the seven assessed designs were viable — the Italian FREMM, the Modified F-100, BAE’s Type 26 and the French FREMM — as the designs were:

most likely to:

- Be compliant with the RAND shipbuilding Principles;

- Meet a 2020 construction start date inclusive of modifications; and

- Sufficiently meeting [sic] the capability requirements.

2.6 The Defence Capability and Investment Committee meeting records state that ‘after discussion, the Secretary [of Defence] agreed that the Italian FREMM (Fincantieri), Modified F-100 (Navantia) and Type 26 (BAE) be recommended to the government for progression through the SEA 5000 Phase 1 Competitive Evaluation Process.’ The meeting records indicated that the Italian FREMM (Fincantieri) and Modified F-100 (Navantia) were considered the two most viable designs and that either the Type 26 or the French FREMM should be progressed as a third option.

Record keeping

2.7 Defence did not retain complete records of the key decisions made during the shortlisting process for the competitive evaluation activity. Records not retained by Defence included the following.

- The basis for the Ship Building Steering Group’s decision to approve seven ship designs for further analysis. It was not clear whether Defence had accepted RAND’s initial shortlist or made the decision to progress analysis on seven ship designs on another basis.36

- The rationale for the Defence Secretary’s (the decision-maker’s) selection of the BAE Type 26 over the French FREMM (DCNS) as the third option.37

2.8 The approach adopted by Defence to its record keeping is not consistent with the July 2014 Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPR) requirements, which applied at that time. Successive iterations of the CPRs have highlighted that maintaining records is one of the ‘fundamental elements of accountability and transparency’ in procurement.38 The requirements for record-keeping are long-standing and appear in section 7 of the CPRs. They state that:

- Officials must maintain for each procurement a level of documentation commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement.

- Documentation should provide accurate and concise information on: the requirement for the procurement; the process that was followed; how value for money was considered and achieved; relevant approvals; and relevant decisions and the basis of those decisions.

- Documentation must be retained in accordance with the Archives Act 1983.39

2.9 Further, the Defence Records Management Policy notes that:

Defence must manage its records in a way that:

a. complies with legislation, standards and government policy;

b. provides for public accountability;

c. supports decision-making; and

d. preserves corporate memory and historical information.

To meet this requirement, all Defence records are:

a. created to support business and meet obligations;

b. captured in digital format and described;

c. made accessible and disclosed where required; and

d. appraised, retained and disposed of in accordance with the principles in this policy.

2.10 In addition to the risk of non-compliance with the CPRs, incomplete record keeping makes it difficult for Defence to: demonstrate that the procurement was conducted with due regard to fairness, probity and value for money; and facilitate scrutiny and review of its procurement processes and decisions, including by the Parliament.40

2.11 Further shortcomings in Defence record-keeping are discussed in paragraphs 2.34 to 2.35, 2.44, 2.63, 2.66 to 2.67, 2.73 and 2.78 of this audit report. These deficiencies raise issues of transparency, accountability and non-compliance with the CPRs and Defence Records Management Policy. Defence’s record keeping has also been identified as an issue in prior ANAO performance audits.41

2.12 The Hunter class procurement is a long-term activity. Given the weaknesses in record keeping identified in this audit, Defence should implement measures to ensure compliance with its Records Management Policy over the life of the program.42

Recommendation no.1

2.13 The Department of Defence ensure compliance with the Defence Records Management Policy and statutory record keeping requirements over the life of the Hunter class frigates project, including capturing the rationale for key decisions, maintaining records, and ensuring that records remain accessible over time.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

2.14 Defence notes the Hunter class frigate project has over 730,000 documents within its record management system (Objective). Of the thousands of documents identified and requested by the ANAO, less than ten documents were unable to be located across the Department.

ANAO comment

2.15 As outlined in paragraphs 2.7 to 2.12 of this audit report, shortcomings in Defence record-keeping are discussed throughout the report. In the context of the competitive evaluation process, Defence did not retain complete records of the key decisions made during the shortlisting process for the evaluation activity, including: the basis for the Ship Building Steering Group’s decision to approve seven ship designs for further analysis; and the rationale for the Defence Secretary’s (the decision maker’s) selection of the BAE Type 26 over the French FREMM (DCNS) as the third option.

2.16 In April 2016, the government agreed (‘first pass’ approval) to: the commencement of the competitive evaluation process for the selection of the head contractor; Defence’s three shortlisted ship designs; and 23 high-level capability requirements.43 The competitive evaluation process was to comprise:

- a risk reduction design study; and

- a Request for Tender (RFT) process.

2.17 Defence advised the government that a suitable design and an affordable and viable build strategy would be presented at the ‘second pass’ government approval stage. In its recommendation to progress the competitive evaluation process, Defence noted that following this process the government would be in a position to choose a preferred option based on the ability to start construction in 2020, the capability requirements, minimal design change and value for money. Government agreed to funding of $289.3 million for the competitive evaluation process.44

2.18 Following the government’s agreement to the procurement approach, Defence did not update the existing October 2014 Acquisition and Support Implementation Strategy (procurement plan)45 or develop a new procurement plan to reflect the change from the approach envisaged in October 2014 and associated risks.46 The development of a formal acquisition strategy or procurement plan was a mandatory requirement of the Defence Procurement Policy Manual in effect at that time. Further, in 2016 first pass advice to government the adoption of a suitable Acquisition and Support Implementation Strategy had been identified by Defence as a mitigation for the risks to implementation (which were assessed as ‘extreme’).

Risk reduction design study

2.19 In August 2016 Defence commenced risk reduction design studies with each of the three tenderers. The studies were conducted to inform Defence’s understanding of the consequences of applying the ‘Australianised’ changes on the reference ship designs and to try to reduce the cost and schedule risk associated with the changes.

2.20 Defence intended to use the information to form the basis of the technical requirements for the RFT. Defence received the risk reduction design study deliverables from the tenderers in May 2017 following release of the RFT. The deliverables were assessed as part of the tender evaluation in November 2017.

Request for Tender for the head contract

2.21 On 28 March 2017 an Endorsement to Proceed (the EtP) with the RFT was approved by the Director-General Future Frigates (civilian Senior Executive Service Band 1 official). According to the EtP, the RFT was:

to establish a long term relationship with a Tenderer so as to assist the Commonwealth to achieve the Project Objectives in the most efficient, effective and innovative manner.

2.22 The RFT document was released on 31 March 2017 to the three tenderers. The conditions of tender provided to the tenderers stated that ‘Tenders will be evaluated utilising the tender evaluation criteria at clause 3.9 to determine the tender that will best support the achievement of the Project Objectives on a value for money basis’. The Minister for Defence Industry announced the release of the RFT, stating that:

The release of the RFT is an important part of the Competitive Evaluation Process which will lead to the Government announcing the successful designer for the Future Frigates in 2018.

…

Three designers—BAE Systems with the Type 26 Frigate, Fincantieri with the FREMM Frigate, and Navantia with a redesigned F100, have been working with Defence since August 2015 to refine their designs.

The three shortlisted designers must demonstrate and develop an Australian supply chain to support Australia’s future shipbuilding industry, and also how they will leverage their local suppliers into global supply chains.

The Government is committed to maximising Australian industry opportunities and participation and this project will contribute to building a sustainable Australian shipbuilding workforce.47

2.23 Responses to the RFT were due on 24 July 2017. On 29 June 2017, Defence wrote to tenderers advising that the closing time for tender response had been extended to 7 August 2017. Tenderers were not informed of the reason for the extension. In December 2022 Defence informed the ANAO that it was unable to locate any documented reason or approval to extend the RFT. All three participants submitted their tenders by 7 August 2017.

2.24 During the RFT process, Defence issued 16 addenda to the tenderers between 7 April 2017 and 28 July 2017. All tenderers were informed of amendments to the RFT documentation at the same time.

Evaluation criteria

2.25 The EtP set out 10 agreed tender evaluation criteria and ‘considerations including value for money’. These considerations included five project objectives that ‘have been developed [to] identify what is required to deliver the outcomes sought by the Government.’ The objectives were:

- deliver nine Anti-Submarine Warfare Frigates (Ships) based on a Military-Off-The-Shelf design with a minimum level of change;

- contribute to a Continuous Naval Shipbuilding industry in Australia;

- maximise Australian Industry Capability;

- commence construction in Adelaide in 2020; and

- remain within the provision48 of the Integrated Investment Program (IIP).49

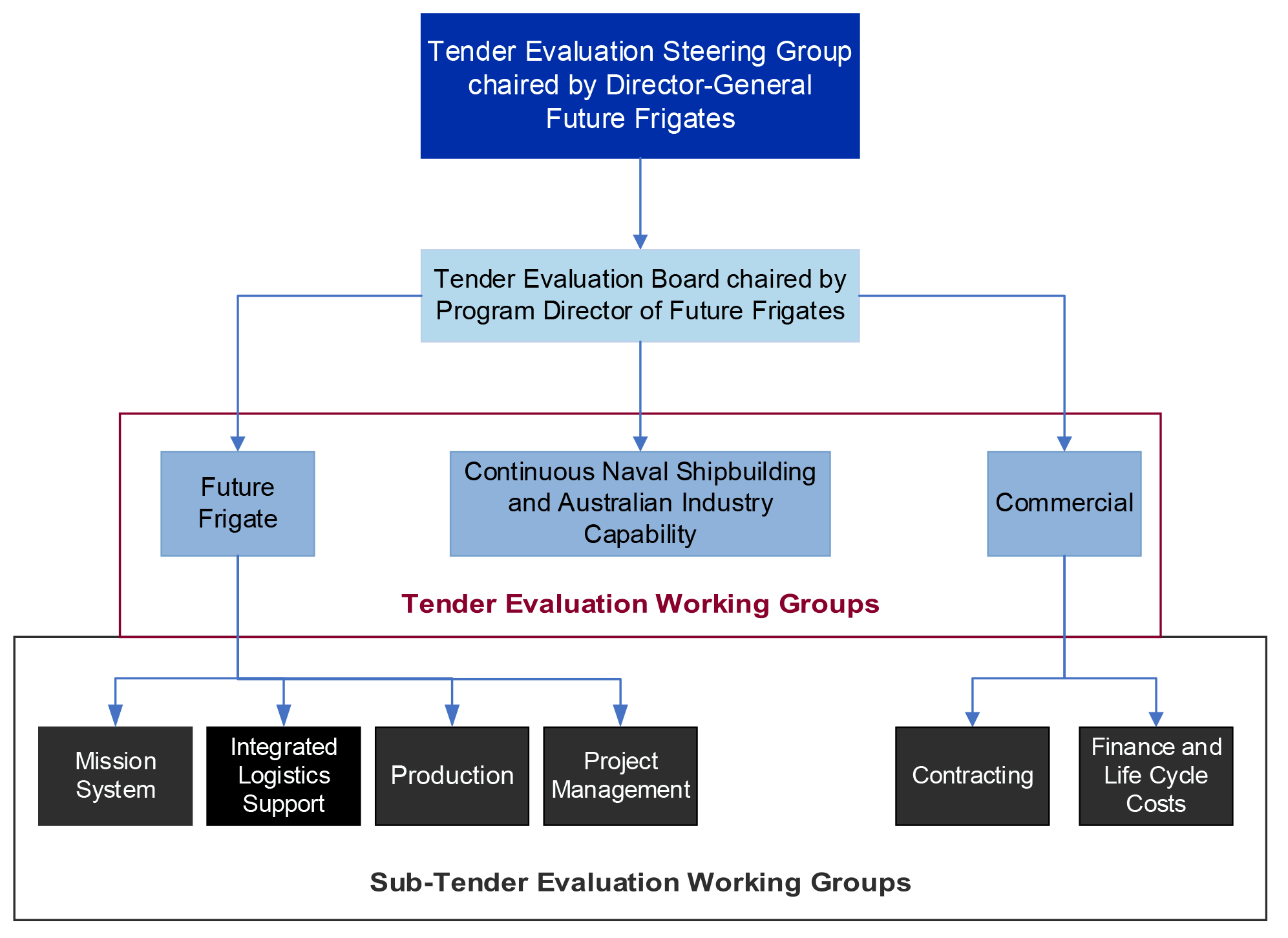

2.26 The objectives aligned with the evaluation criteria, as shown in Figure 2.1 below. The 23 high-level capability requirements (discussed in paragraph 2.16) were included under the ‘tendered mission system will meet the Commonwealth’s capability requirements’ evaluation criterion.

Figure 2.1: Alignment of project objectives and tender criteria

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Defence documents.

2.27 In the EtP, Defence documented an assessment of the risks to each of the five project objectives and the risk treatments.

- Three project objectives were assessed as high risk. These were: ‘to deliver nine Anti-Submarine Warfare Frigates (Ships) based on a Military-Off-The-Shelf design with a minimum level of change’; ‘contribute to a Continuous Naval Shipbuilding industry in Australia’; and ‘remain within the provision of the Integrated Investment Program’.

- Two project objectives were assessed as medium risk. These were: ‘maximise Australian Industry Capability’; and ‘commence construction in Adelaide in 2020’.

2.28 Enclosures to the EtP included signoffs from the probity advisor for the project (the Australian Government Solicitor, AGS)50 and the legal advisor for the procurement (Ashurst). In summary, the legal advisor did the following.

- Noted risks with regards to the RFT approach, including the lack of a statement of work51, operational and performance specification documents, and limitations to the achievement of tender quality pricing.

- Indicated that given this approach, the tenders would not represent binding offers from the participants to enter into a contract, that were capable of acceptance by the Commonwealth. The tenders would instead include a range of information and proposals that could, with further negotiation and development, form the basis of a binding offer in due course.

- Noted uncertainties regarding the shipyards, workforce arrangements, combat management system, some aspects of continuous naval ship building and Australian Industry Capability, and pricing risks.

2.29 The RFT also outlined key assumptions for the tenderers to rely on for the purpose of developing their tenders, as outlined in Table 2.1. These assumptions aligned with areas of uncertainty identified by the legal advisor in reviewing the EtP.

Table 2.1: Key Assumptions in the Request for Tender

| Area | Assumption a |

| Drumbeat | 24 months between the start of construction of each ship. |

| Shipyard | The tenderers will be provided with a facilities assumptions document. The shipyard and associated infrastructure will be Government Furnished Facilities and the contractor will operate the shipyard including for other Commonwealth projects in the shipyard. |

| Ship batches | The ships will be built in three batches, with three ships in each batch. |

| Responsibility for workforce | The contractor will not be required to engage any particular shipbuilding workforce. |

| Combat Management System | The Commonwealth will specify a combat management system after tender lodgement, which will be provided to the contractor as mandated Government Furnished Material. For the purposes of the tender the tenderers are to assume an Aegis combat management system, representing the more difficult option for physical integration into the platforms. |

Note a: Following the release of the RFT, two of the five key assumptions changed. The Osborne shipyard was specified as the location of construction. Defence introduced the purchase of ASC Shipbuilding as a contractual requirement, as noted at paragraph 1.13.

Source: Department of Defence.

Tender Evaluation Plan

2.30 Defence’s 2016 Defence Procurement Policy Manual — which was in effect at the time the Tender Evaluation Plan (TEP) was developed — provided that tender evaluation plans must be prepared for all complex procurements and all military significant procurements as part of a major or minor project. The TEP was expected to be ‘the planning and control document for the management and conduct of the tender evaluation’.

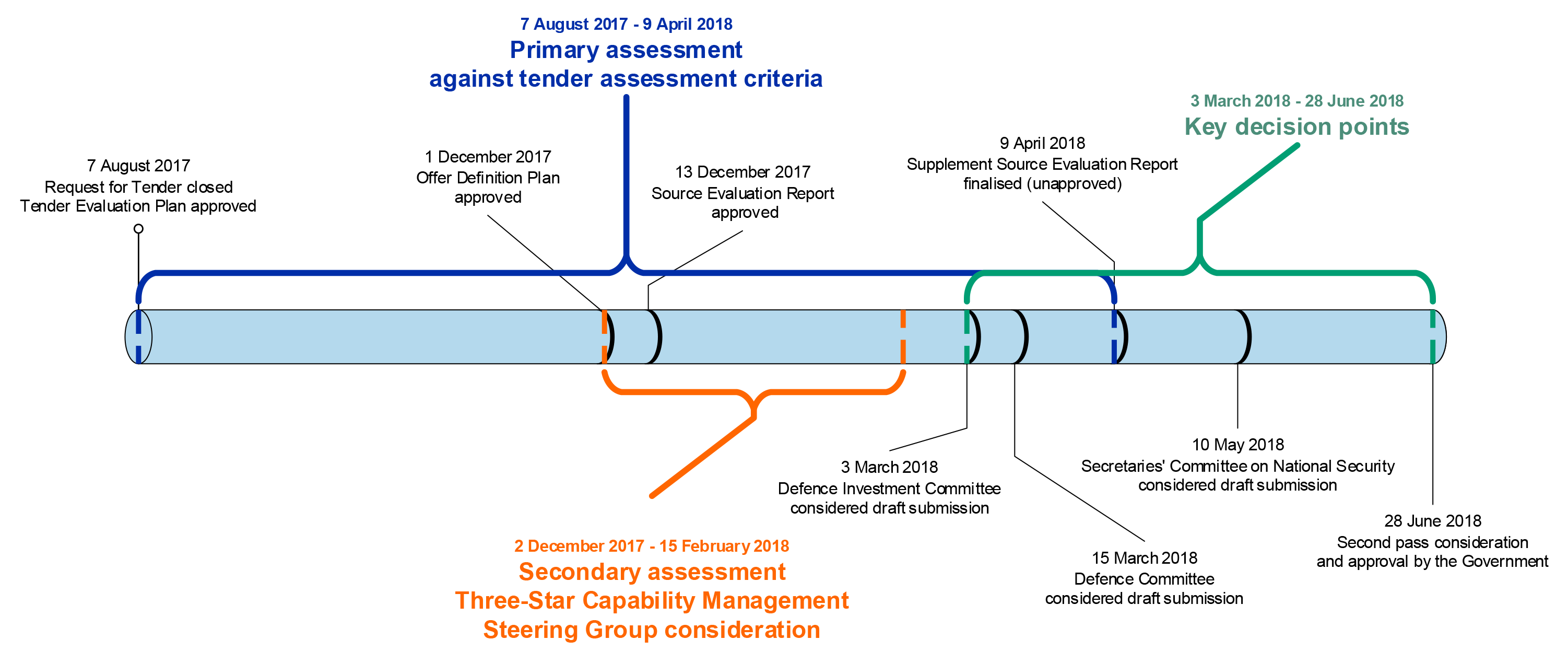

2.31 The Future Frigate TEP was signed on 7 August 2017, the day the tender closed, by the Acting Director-General Future Frigates (acting SES Band 1/one-star equivalent). The plan established the Tender Evaluation Organisation (see Figure 2.2 below) and an Expert Advisory Panel.52

Figure 2.2: Elements of the Tender Evaluation Organisation

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Defence documents.

2.32 The Future Frigate TEP set out roles, responsibilities, and the process to be followed for the evaluation of tenders (including tender registration, managing late tenders, conducting an initial screening process, and rules regarding access to tenders). Regarding the assessment of value for money of the tenders received, the TEP stated that:

The TEP does not require the Tender Evaluation Organisation (TEO) to conduct a comparative evaluation of tenders and to determine a ranking of tenders based on a value for money assessment of the tenders. Rather the TEO is to provide Government with its assessment of the acceptability to the Commonwealth of the tenders against each of the evaluation criterion. Using the acceptability assessment it is proposed that Government will consider the value for money of the tenders.

2.33 AGS provided a formal sign-off for the TEP, stating that it had identified ‘no probity or legal process issues with the contents of the Evaluation Plan’. Previously, AGS had provided input on the lack of a process for assessing value for money in the draft TEP (dated 2 March 2017).

We understand that the TEP [Tender Evaluation Plan] does not require the TEO to make a value for money assessment. As this is a procurement process, a VFM [value for money] decision will need to be made at some level of government – in our view this process should be outlined in the TEP. We suggest that the intended process to be undertaken be explained in the TEP. If there is a more detailed process to be conducted within government for the selection of the preferred tenderer then we suggest that it be detailed in the TEP.

2.34 The TEP did not document how the evaluation process would address the core rule of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) — achieving value for money — other than to say that ‘it is proposed that Government will consider the value for money of the tenders’. Paragraph 4.4 of the March 2017 CPRs, which applied at the time, provided that: ‘Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs. Officials responsible for a procurement must be satisfied, after reasonable enquires, that the procurement achieves a value for money outcome [emphasis in original].’ Further, the ‘Defence Procurement Policy Manual 2016’, which applied at the time, reiterated the CPR requirements and highlighted the requirement for comparative analysis of costs and benefits in assessing value for money:

The CPRs provide that Value for Money is the core principle underpinning Australian Government Procurement and the application of this principle requires a comparative analysis of all relevant costs and benefits of each proposal throughout the whole procurement cycle (whole-of-life costing).

Value for Money is not limited to a consideration of capability versus price, or ‘cheapest price wins.’ Value for money requires consideration of Australian Government policy, specifically values such as open competition, efficiency, ethics and accountability. The CPRs outline these policies in further detail. Officials conducting procurement should be aware that the overall goal of the procurement process is to provide a value for money recommendation to the delegate. [emphasis in original]

2.35 Defence did not document the rationale for the Future Frigate TEP not requiring a value for money assessment, comparative evaluation of the tenders, or ranking of tenders.53 This was a further shortcoming in record-keeping for the procurement. There is no Defence record of the department seeking advice from the Department of Finance on its selected procurement approach and compliance with the CPRs.

Assessment against the Tender Evaluation Plan

2.36 Tenders were assessed in accordance with the Tender Evaluation Plan (TEP) following the close of the request for tender (RFT) on 7 August 2017.

2.37 The Source Evaluation Report54 was approved by the delegate (Deputy Secretary, Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group) on 13 December 2017. The report set out the Tender Evaluation Board’s overall assessment of tender compliance55 and risk56 for each of the 10 criteria outlined in the RFT and TEP. All tenderers were found to be ‘acceptable with changes’, with tenders largely meeting compliance requirements and resulting in a combination of medium–high risks across most criteria, with two extreme risks identified in the assessment of the BAE Systems’ Type 26 design. A summary of the results is set out in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Summary of the overall assessment of tender compliance and risk

| Criterion | BAE Systems | Tenderer A | Tenderer B |

| Contribution to a Continuous Naval Shipbuilding Industry | Meets Requirements High Risk | Meets Requirements High Risk | Meets Requirements High Risk |

| Maximising Australian Industry Capability | Meets Requirements High Risk | Meets Requirements High Risk | Meets Requirements High Risk |

| Tendered Mission System | Meets Requirements Medium Risk | Meets Requirements Medium Risk | Marginal (closer to Meets Requirements) Medium Risk |

| Commencement of Prototyping and Construction in Adelaide | Meets Requirements (closer to Marginal) Extreme Risk | Meets Requirements High Risk | Meets Requirements High Risk |

| Deliver nine ships based on the RSD with Minimum Change | Meets Requirements Extreme Risk | Meets Requirements (closer to Marginal) Medium Risk | Meets Requirements Medium Risk |

| Integrated Logistics Support program proposal | Meets Requirements (closer to Marginal) Medium Risk | Meets Requirements Medium Risk | Meets Requirements (closer to Marginal) Medium Risk |

| Project management proposal | Meets Requirements Low Risk | Meets Requirements (closer to Marginal) Low Risk | Meets Requirements (closer to Marginal) Low Risk |

| Head Contract Compliance | Does not meet requirements – Moderate

Medium Risk |

Does not meet requirements – Significant

High Risk |

Marginal

Low Risk |

| Pricing and Payment arrangements | Compliance with pricing models: Does not meet requirements (significant)

High Risk |

Compliance with pricing models: Does not meet requirements (moderate)

Medium Risk |

Compliance with pricing models: Marginal High Risk |

| Financial and Corporate Viability, Capability and Capacity | Meets Requirements

Medium Risk |

Marginal

Medium Risk |

Meets Requirements

Medium Risk |

Source: Defence.

2.38 In accordance with the TEP, the Source Evaluation Report did not include a value for money assessment and did not recommend a preferred tenderer.

2.39 Following the 13 December 2017 delegate approval of the Source Evaluation Report, the probity advisor (AGS) issued a probity sign-off on 21 December 2017, confirming that from a probity perspective the assessment of tenderers in the Source Evaluation Report was ‘fair and defensible’. Defence should have ensured that the probity sign-off was available to the delegate (the Deputy Secretary CASG) at the time of the delegate’s consideration of the tender evaluation report.

Offer Definition and Improvement Activities

2.40 Prior to finalisation of the Source Evaluation Report (SER), Defence commenced Offer Definition and Improvement Activities with all three tenderers. The SER contained advice to the SER delegate (the Deputy Secretary, Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group) that:

With the approval of the SER delegate, the Project has entered into Offer Definition with all three tenderers prior to Second Pass. Offer Definition will be used to further explore key issues and risks identified in tender evaluation, and seek to mitigate short term Project risks.

2.41 The SER delegate’s approval to proceed with offer definition activities was provided by email on 30 November 2017, with Defence commencing offer definition activities with all three tenderers on the same day.

2.42 An Offer Definition Plan was approved on 1 December 2017 by the offer definition delegate, the Director-General Future Frigates (SES Band 1/one-star equivalent). The plan stated that the objectives of the Offer Definition and Improvement Activities were to:

- improve and maximise value for money, which is achieved through competitive tension and providing feedback on selected aspects of the tendered offers;

- enable the tenderers to better understand Defence’s requirements and Defence to better understand the tenders, with the aim of refining the products to be contracted;

- minimise risk, by giving the Commonwealth the opportunity to identify and agree potential risk treatments with each tenderer; and

- progress contract documents so the Commonwealth and any subsequent preferred tenderer will have fewer issues to resolve during contract negotiations in the lead up to contract signature.

2.43 Tenderers provided offer definition responses between 12 December 2017 and 28 February 2018. Defence reported the outcomes of the offer definition process in a ‘Source Evaluation Report Supplement’. That report provided a further assessment of each tenderer against eight of the 10 tender evaluation criteria and highlighted six areas of change between the Source Evaluation Report and the offer definition outcomes.57 The report concluded that the overall assessment of tenderers remained unchanged and all tenders had ‘the potential to achieve the project objectives, but with different strengths and weaknesses, and areas of discrimination.’58

2.44 On 9 April 2018, the Source Evaluation Report Supplement was finalised by the Project Director. Defence has not retained a record of the approval of this report by the offer definition delegate or the Source Evaluation Report delegate.59 Further, the Source Evaluation Report Supplement did not include a value for money assessment (which had been identified as an objective of the Offer Definition and Improvement Activities) or recommend a preferred tenderer. As discussed in paragraphs 2.32 to 2.35, the approach to tender evaluation adopted by Defence was not consistent with the CPRs or the Defence Procurement Policy Manual 2016, which applied at the time. Further, and as discussed in paragraphs 2.7 to 2.9, these and other shortcomings in record-keeping raise issues of transparency, accountability and non-compliance with the CPRs and Defence Records Management Policy.

2.45 The probity advisor (AGS) signed off the Source Evaluation Report Supplement, confirming that: the evaluation of Offer Definition deliverables had been conducted in accordance with the Offer Definition Plan, RFT and the Tender Evaluation Organisation; and that the assessment in the Source Evaluation Report Supplement was ‘fair and defensible’ from a probity perspective. The AGS sign off did not include commentary in relation to value for money.

Management of probity

2.46 The November 2016 Legal Process and Probity Plan reflected the procurement approach agreed by the government in April 2016 and set out ethical and probity standards to be followed by Defence officials. The Director-General Future Frigates was responsible for ensuring compliance with the plan. The plan set out the following.

- Applicable legislative and regulatory requirements (such as the Defence Accountable Authority Instructions made under the PGPA Act).

- Instructions on how to work with tenderers.60

- Responsibilities for the identification and management of conflicts of interest.

- Records management responsibilities, including the maintenance of a register of conflicts of interest, a register of gifts and hospitality61, and an audit trail.

2.47 Defence’s probity register recorded that 1571 officials received a probity briefing or returned a conflict of interest declaration between February 2016 and January 2019. The register did not contain sufficient information to determine whether all members of on-site liaison teams received probity training or briefings prior to commencing their roles. For the 1571 entries, ANAO analysis indicates the following.

- There were 72 instances of a conflict of interest or confidentiality declaration not being completed. For these 72 cases, there were 52 instances where document management system access was reported as being removed and 20 instances where there is no report of action taken.

- There were 32 instances where a probity briefing was not recorded. For these 32 cases, there were 28 occurrences reported of the person’s access being removed.62 There were four instances of personnel not completing a required probity briefing and not being recorded as having their access removed.

2.48 Defence recorded interactions between Defence officials and tenderers or other relevant parties between August 2016 and November 2018 on a register of communications. The project register included a gift register (which was a subset of the communications register) with six entries. Five of the six entries were for gifts received by the on-site liaison teams and one entry was for a gift received by the Project Director.63 ANAO review of Defence records identified that BAE Systems notified Defence that it provided hospitality valued at AUD $340 to the General-Manager Ships and Director-General Future Frigates. Receipt of this hospitality was not recorded by Defence in the project register or the departmental gifts and benefits register.64 There is no record of Defence’s management of probity in relation to this event.

Management of probity issues

2.49 During the competitive evaluation process, the probity advisor (AGS) provided advice on a range of topics including conflicts of interest, protocols for the on-site liaison teams, communication with tenderers, the tender evaluation process, media, and requests for information.

2.50 Defence records show that five of the eight recorded probity issues had been reported to the Project Director by project staff.65 Of the remaining three incidents66, AGS was aware of two incidents. The remaining incident was reported through the SEA 5000 probity mailbox.67 These probity incidents and their treatments were not recorded in any register.

2.51 In signing off the competitive evaluation process, the probity advisor reported to Defence that:

Key legal process and probity issues, such as identifying and managing conflicts of interest, ensuring the fair and equitable treatment of tenderers, and ensuring the protection of confidential information have, in our view, been managed appropriately throughout the CEP.

| Opportunity for improvement |

| 2.52 Prior to obtaining sign-off by the probity advisor in a procurement context, Defence should confirm that all probity matters have been drawn to the attention of the probity advisor. |

Did Defence effectively advise government?

Defence’s advice to government at first pass was timely and informative. However, its recommendation to include the BAE Type 26 design in the competitive evaluation process (CEP) as the third option, instead of the alternate, was not underpinned by a documented rationale.

At second pass, Defence’s advice to government on the selection of the preferred ship design was not complete. Defence did not draw the following matters to government’s attention.

- Contrary to the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), a value for money assessment had not been conducted by Defence officials. Defence’s assessment was against the high-level capability requirements.

- Under the Tender Evaluation Plan (TEP) Defence expected government to consider the value for money of the tenders.

- A 10 per cent reduction to tendered build costs had been applied by Defence. The reduction had not been negotiated with tenderers.

- Sustainment cost estimates had not been prepared for government consideration as required by the Budget Process Operational Rules applying to Defence.

In its assessment, which was included in Defence’s second pass advice to government, the Department of Finance (Finance) drew attention to the 10 per cent reduction to tendered build costs and other limitations in Defence’s advice on costs. Finance did not comment on Defence’s lack of a value for money assessment, compliance with the CPRs or quality of advice regarding value for money.

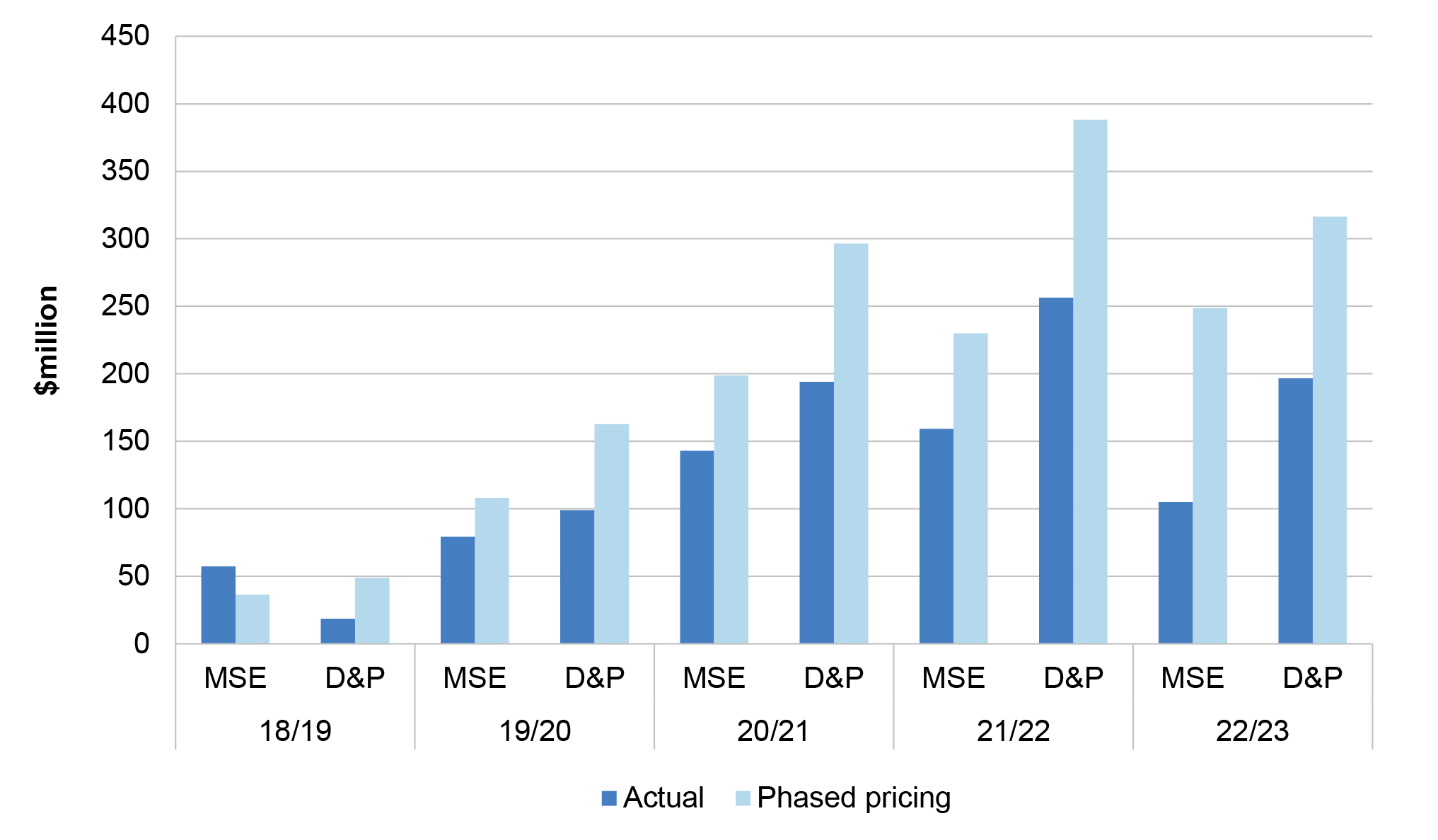

Advice provided to government at ‘first pass’