On the morning of 8 September 1923, thirteen destroyers of Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 11 departed San Francisco for a two-day cruise to San Diego. They were returning home after a escorting Battle Division 4 from Puget Sound to San Francisco. The DesRon comprised the five ships of Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 33, with Delphy (DD-261) out front, followed by S.P. Lee (DD-310), Young (DD-312), Woodbury (DD-309) and Nicholas (DD-311); six ships from DesDiv 31, with Farragut (DD-300) followed by Fuller (DD-297), Percival (DD-298), Somers (DD-301), Chauncey (DD-296) and Kennedy (DD-306); and three ships from DesDiv 32, Paul Hamilton (DD-307), Stoddert (DD-302) and Thompson (DD-305). The warships conducted tactical and gunnery exercises en route, including a competitive speed run of 20 knots. Later in the day, as weather worsened, the ships formed column on the squadron leader Delphy.

That evening, around 2000 hours (8 p.m.), the flagship broadcast an erroneous report–based on an improperly interpreted radio compass bearing–showing the squadrons position about nine miles off Point Arguello. An hour later, the destroyers turned east to enter what was thought to be the Santa Barbara Channel, though it could not be seen owing to thick fog. Unfortunately, a combination of abnormally strong currents (caused by the extremely severe earthquake in Japan on 2 September which destroyed much of Tokyo and Yokohama) and navigational complacency led the squadron onto the rocks off Pedernales Point, near Honda, just north of Point Arguello.

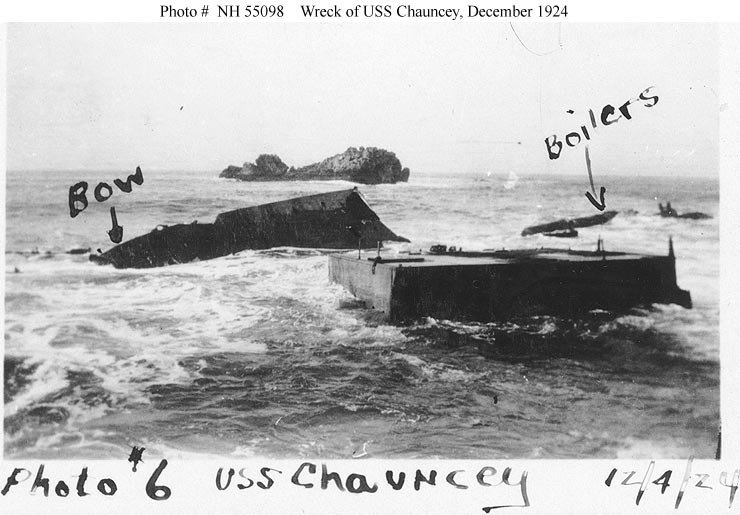

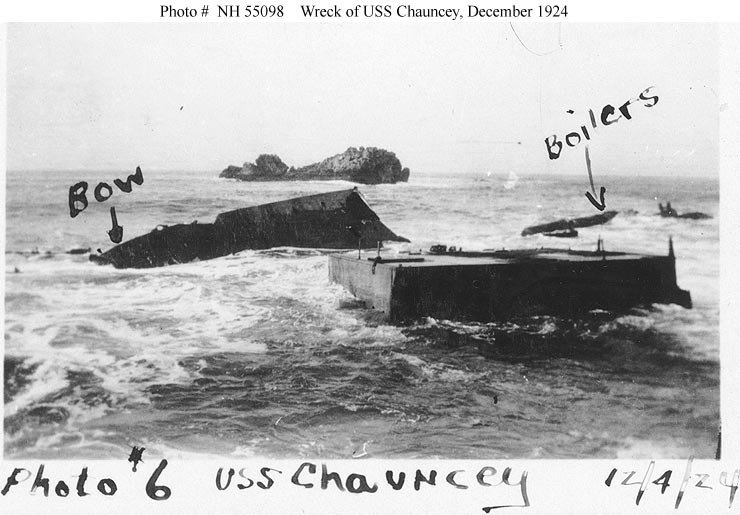

Just after turning, Delphy struck the rocks at 2105, plowing ashore at 20 knots. She was followed by S.P. Lee, which hit and swung broadside against the bluffs. Young piled up adjacent to Delphy and capsized, trapping many of her fire and engine room crew below. While Woodbury, Nicholas and Fuller struck reefs and ran aground offshore, Chauncey ran in close aboard Young. Alarm sirens slowed Somers and Farragut enough so they just touched ground before backing off while the five other destroyers steered completely clear.

Although seven destroyers were eventually wrecked by the pounding surf, the slow, cumulative damage gave the crewmen time to escape. Rescue parties were organized, small boats and local fishing boats picked up swimmers, and life lines strung to shore allowed the rest to wade to safety. Despite delays–the last sailors were not rescued until the afternoon of 9 September–only 23 men were lost, 20 in Young and 3 in Delphy.