By William H. Thiesen, Ph.D. Coast Guard Atlantic Area Historian

“By the way, Admiral Smith recently commended the Escanaba, its officers, and men, for brilliant rescue work. The ship saved about 150 men who were cast into a very cold sea. Most of the men were helpless due to the cold, their hands and feet were frozen, many were unconscious, and only one group were in a boat.”

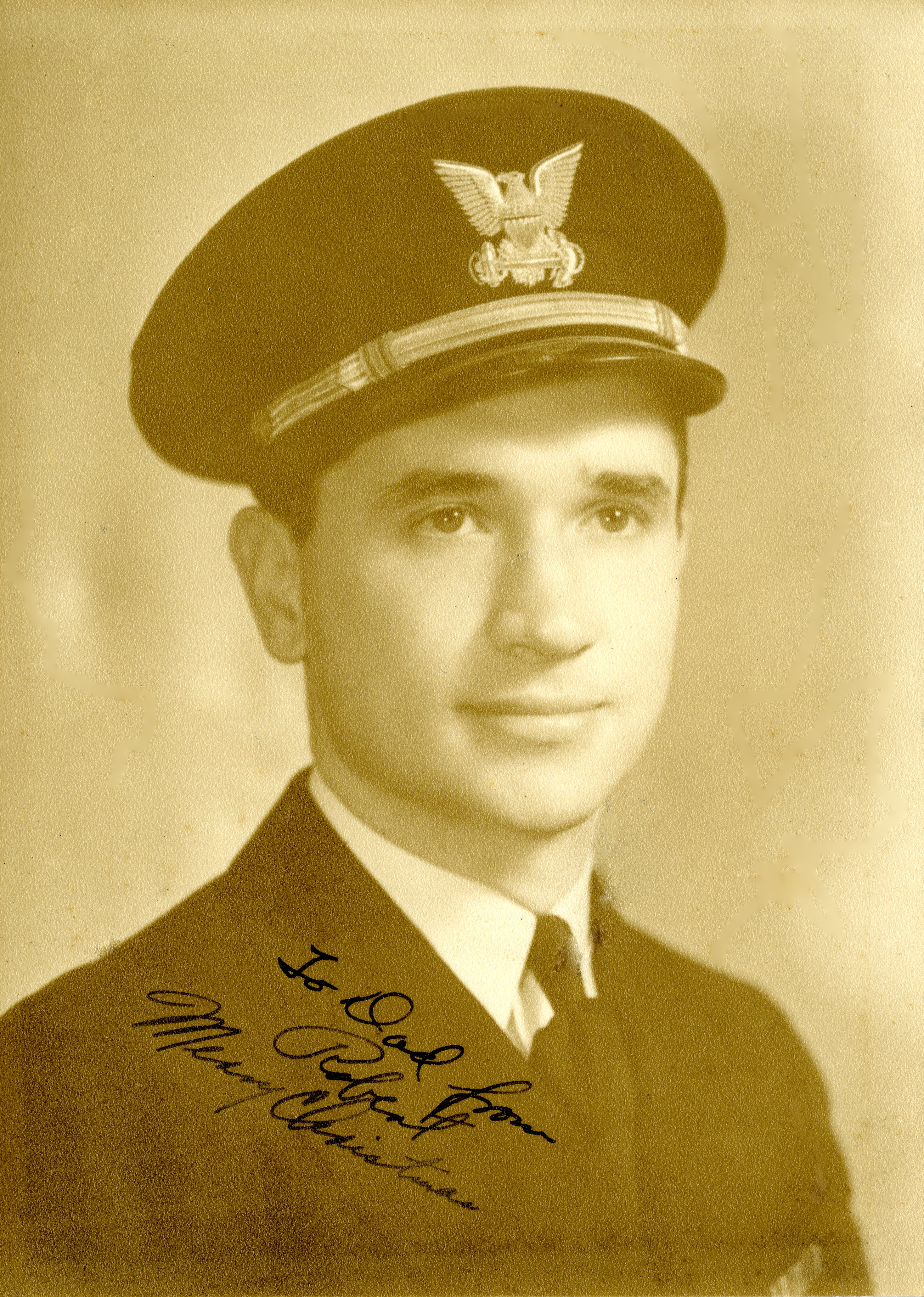

In the April 1943 letter home quoted above, Lt. Robert “Bob” Prause, Jr., described the rescue of victims of a U-boat attack. The event took place in the icy waters of Greenland 80 years ago during the Battle of the Atlantic.

Born in 1915, Bob Prause grew up in in Norfolk, Va., where he attended Matthew Fontaine Maury High School and became an active member of the school’s math, science and literary clubs. After a year of studies at Norfolk’s Old Dominion University, Prause followed his passion for technical studies and entered the Coast Guard Academy with the class of 1939. Prause graduated from the Academy then served on board the cutters Modoc and Onondaga.

In early 1942, Prause received orders that would forever associate his name with a famed cutter of World War II. He shipped out to serve as executive officer on board the Escanaba, home-ported in Grand Haven, Michigan. In June, Escanaba changed stations from the Great Lakes to Boston to become part of the Coast Guard’s Greenland Patrol. Over the course of the next year, Escanaba served as an escort for convoys steaming between U.S. and Canadian ports, and on to Greenland in arguably the worst sea and weather conditions in World War II.

On Monday, June 15, 1942, an event took place that made a lasting impression on Prause. While escorting a convoy from Nova Scotia to Greenland, a U-boat attack sank the passenger steamer Cherokee, plunging nearly 170 passengers and crew into the bone-chilling seas. Within minutes, the frigid water temperature had incapacitated Cherokee’s survivors. Desperate to rescue as many men as possible, Prause dangled headfirst over the side of the cutter while his shipmates held his legs. In spite of the threat of submarine attack and heavy seas, Prause and Escanaba managed to save 22 survivors.

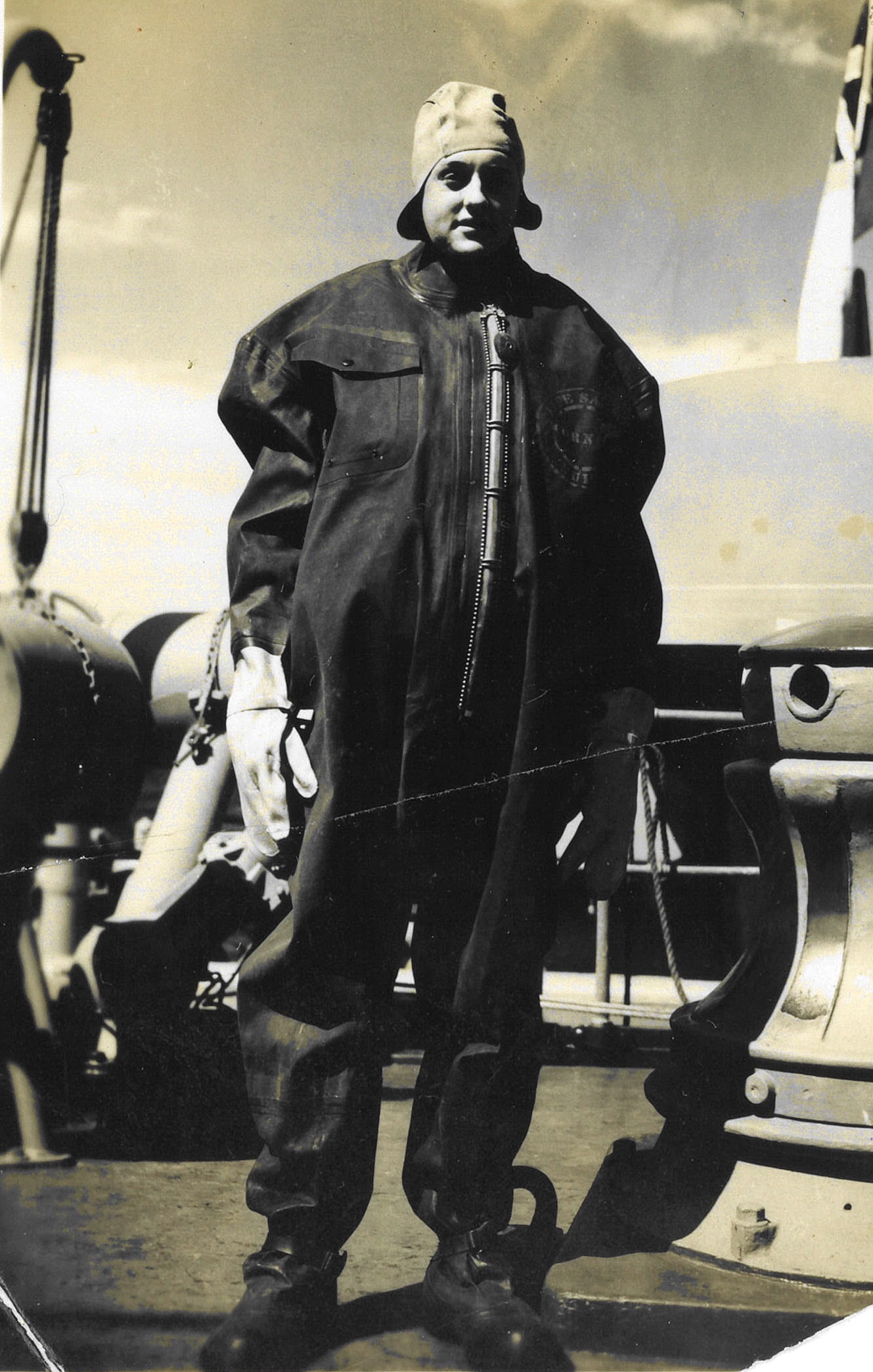

With high seas and icy water, the obstacles to saving victims afloat in Greenland waters seemed insurmountable. Nevertheless, the challenge of saving as many lives as possible motivated Prause to develop a system of tethered rescue swimmers equipped with rubber exposure suits, which insulated the swimmers from the cold. Next, he worked with three crewmembers, including Cook Forrest Rednour and Officer’s Steward Warren Deyampert, who volunteered to serve as swimmers. Prause drilled the men and their support crews so that the swimmers and the retrievers on deck could perform their duties smoothly from the cutter’s rolling deck in blackout conditions. In his letter home, Prause briefly described his retriever system:

With high seas and icy water, the obstacles to saving victims afloat in Greenland waters seemed insurmountable. Nevertheless, the challenge of saving as many lives as possible motivated Prause to develop a system of tethered rescue swimmers equipped with rubber exposure suits, which insulated the swimmers from the cold. Next, he worked with three crewmembers, including Cook Forrest Rednour and Officer’s Steward Warren Deyampert, who volunteered to serve as swimmers. Prause drilled the men and their support crews so that the swimmers and the retrievers on deck could perform their duties smoothly from the cutter’s rolling deck in blackout conditions. In his letter home, Prause briefly described his retriever system:

… we used the Escanaba retriever method of rescue which I myself designed and tested out. A man in a rubber suit with a parachute harness about him and a line attached is sent over the side. The retriever swims out, ties on another line about the victim or raft and it’s hauled into the ship’s side.

On Wednesday, February 3, 1943, a convoy bound from Newfoundland to Greenland provided the first test of Prause’s system. Cutters Escanaba, Tampa and Comanche served as escorts for a group of three steamers, including the U.S. Army Transport Dorchester, which carried 904 passengers and crew. A U-boat attacked at 1:00 a.m. the next morning and a torpedo ripped through Dorchester’s hull. The transport sank in 20 minutes, sending hundreds of passengers and crew into the icy waters.

By the time Escanaba arrived on scene, Dorchester had vanished into the frigid seas. The transport’s life preservers were equipped with blinking red lights to help rescuers locate victims at night. These red lights dotted the water’s surface for miles. The service required cutters to enforce blackout conditions during nighttime operations, but Prause’s swimmers donned their exposure suits while deck crews prepared to retrieve survivors.

The tethered rescue swimmer operations were far more effective in recovering survivors than any previous attempts. Equipped with their exposure suits, retrievers Rednour and Deyampert swam out to the Dorchester’s survivors and determined whether they were still alive while Escanaba’s deck crew hauled-in those still living. By the end of the eight-hour operation, Escanaba had saved 133 lives, far more than the 22 rescued from USS Cherokee. Prause’s tethered rescue swimmer system had worked.

The glow of Prause’s success proved short lived. In June, Escanaba joined cutters Storis and Raritan to escort a convoy bound from Greenland to Newfoundland. At 5:00 a.m. on Sunday, June 13, almost a full year after the Cherokee rescue, Escanaba fell victim to what many believe was a torpedo attack. In minutes, she exploded and sank, taking the lives of nearly all her crew. Only three survivors remained in the water after the explosion, including Prause — now ironically the victim and not the rescuer. The crew of cutter Raritan threw him a line, pulled him on deck and took him below for medical attention. In the infirmary, Prause lost consciousness and died. On board Raritan, 80 years ago, Lt. Robert Prause was given full military honors and buried at sea.

The April 1943 letter received by his parents proved the last time they would hear from their son. For their heroic efforts, Bob Prause, Forrest Rednour and Warren Deyampert posthumously received the Navy & Marine Corps and Purple Heart medals, and Rednour and Deyampert were honored as cutter namesakes. They were members of the long blue line and their tethered rescue swimmer system served as the Coast Guard’s first successful cold-water rescue method.