By William H. Thiesen

Historian, Coast Guard Atlantic Area

At the time of the visit of the party, in summer of 1911, heaps of the bodies of the slain still lay on the ground, mute witnesses of the sad fate that had overtaken these beautiful birds.

Henry W. Henshaw, Chief, U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey, 1911

Henry Henshaw was not only chief of the federal bureau overseeing threatened species over 100 years ago; he was also the nation’s leading ornithologist (expert on birds). In this capacity, he reported on the poaching of wild seabirds on the remote and uninhabited Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

During the 1800s, American expansion led to the exploitation of previously uninhabited lands. Moreover, the voracious appetite for wild animals for food, clothing, souvenirs, and sport, threatened the existence of many species inhabiting the land and waters of the United States. However, by the late 1800s, the U.S. had also become a world leader in protecting species from poaching and unregulated catches.

During the 19th century, one of the missions of the Revenue Cutter Service – a precursor service of the Coast Guard – was protecting mammals and marine life. The service began protecting natural resources in 1822 by guarding forests of federal naval timber in Florida. However, when the U.S. acquired Alaska in 1867, it also assumed the mission of protecting wildlife populations, such as the Northern Fur Seal inhabiting the Bering Sea.

In 1899, an Act of Congress transferred the one-time Arctic whaler turned U.S. naval vessel, USS Thetis, to the Revenue Cutter Service. Thetis had been a naval vessel since 1884, when it rescued the ill-fated Greely Expedition to Ellesmere Island, just north of the Arctic Circle. On March 16, the Treasury Department notified the Revenue Cutter Service that the Navy would transfer the Thetis, with all its boats, equipment, and gear. In April, the service ordered Thetis to Seattle, its new homeport. Ironically, the ship originally designed to hunt marine life spent the next five years enforcing regulations to protect it in Alaska.

In March 1904, Cutter Thetis’s annual patrol of Alaska’s Bering Sea was interrupted when its commanding officer, Capt. Oscar Hamlet, received orders to proceed to Hawaii. These orders initiated Thetis’s mission to protect yet another species from illegal poaching—wild seabirds. That year not only marked an expansion of the service’s mission to protect wildlife from illegal poaching, but it also marked the beginning of a long relationship between Hawaii and the Coast Guard.

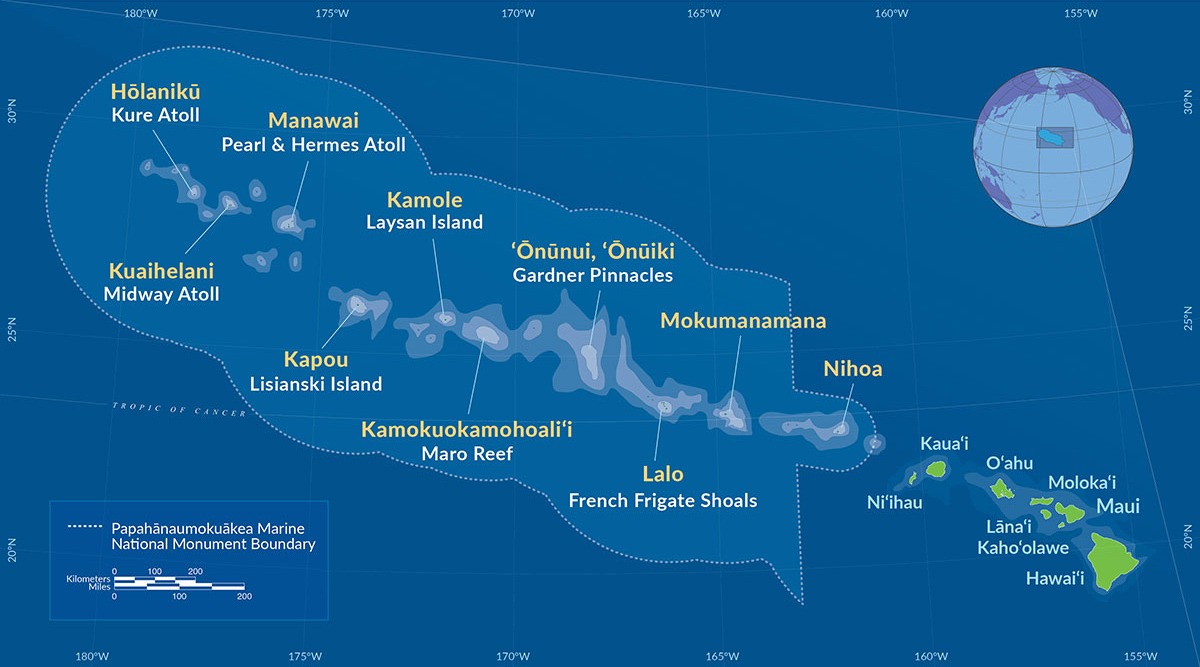

In May, when Thetis arrived in Honolulu, Hamlet took on supplies and sailed for the remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands located hundreds of miles from the main Hawaiian Islands. In mid-June, after delivering supplies to a bird monitoring station at Midway Island, Thetis arrived off Lisianski Island. The cutter’s landing party discovered 77 Japanese hunters slaughtering seabirds and albatrosses. Thetis crewmen arrested the poachers and took them back to Hawaii for adjudication.

In early July 1904, Thetis sailed north for Alaska, where it returned to its normal Bering Sea patrol duties. From late 1905 to early 1906, the cutter was of commission and, from 1906 to 1909, it cruised only in the waters of Alaska and Washington State.

One of the nation’s greatest movements to preserve wild lands and wildlife took place under President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt. Beginning in 1901, Roosevelt established 150 national forests, four national game preserves, five national parks, 18 national monuments, and 51 federal bird reservations. In all, Roosevelt set aside a staggering 230 million acres of public land, far exceeding the record of any president serving before or since.

Late in his presidency, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 1019 protecting bird-nesting islands northwest of Hawaii including French Frigate Shoals, Kure Atoll, Laysan Island, Lisianski Island, Midway Island, and several other uninhabited islands. These islands comprised Roosevelt’s Hawaiian Islands Reservation where, during certain seasons, millions of seabirds nested and reared their young. Roosevelt’s order made it unlawful for any person to hunt, trap, capture, willfully disturb, or kill any bird of any kind whatever, or take the eggs of such birds within the limits of this reservation except under such rules and regulations as may be prescribed from time to time by the Secretary of Agriculture. Warning is expressly given to all persons not to commit any of the acts herein enumerated and which are prohibited by law.

In May 1909, Japanese hunters returned to the remote islands northwest of the Main Islands. This time, they landed on Laysan and the hunt was underway. With no law enforcement services on hand to apprehend the poachers, many bird populations were decimated. By the fall, the feather hunters had killed hundreds of thousands of birds. While albatrosses were the chief target of the killing, the poachers killed dozens of other species.

Later that year, Thetis’s crew received orders to Hawaii for permanent duty. On Christmas Day 1909, the revenue cutter arrived in Hawaii and established the Honolulu Station. Under the command of Capt. William Jacobs, it initiated an annual deployment to the Territory of Hawaii. Revenue cutters had visited the sovereign Kingdom of Hawaii as early as 1849; however, Thetis was the first revenue cutter stationed there. Thetis had become Hawaii’s first cutter.

In January 1910, Thetis arrived at Laysan Island and stopped the killing. The cutter also visited Lisianski Island and arrested more Japanese poachers—in all, the cutter apprehended 23 poachers and transferred them to Honolulu for trial. The bales of wings cut off over a quarter million birds were confiscated. In all, the poachers had killed nearly a million birds to send to Japan for processing before shipping the plumage to European clothing producers. On the open market, the feathers they baled would have fetched $112,500 (worth $3.2 million in 2021 dollars).

In August, Thetis returned to Laysan to ensure the poaching had stopped. The slaughter that took place earlier in the year was evident everywhere. A storehouse used by the poachers was still standing and filled with thousands of pairs of albatross wings. Had the poachers not been stopped, no doubt they would have killed every bird nesting on Laysan, Lisianski and other bird nesting islands.

Thetis made several cruises to Laysan and Lisianski islands in 1911. In January, the cutter received orders to convey a Department of Agriculture party to Laysan. In April, Thetis set sail from Honolulu with the research expedition. During the party’s visit, heaps of bird carcasses still lay on the ground from the massacre a year before and the native Laysan Duck specie had been reduced to only 11 survivors. Thetis returned the party to Honolulu in July.

In early 1912, Thetis arrived at the Honolulu station and remained there until June, when it returned to Alaska. However, in October, it sailed south to Honolulu and, in December, sailed for Laysan Island. The cutter carried an expedition from the Department of Agriculture visiting bird reservation islands under the direction of the Governor of Hawaii, who also sailed aboard the cutter.

Thetis made several cruises to Lisianski, Necker, and Bird islands and French Frigate Shoals in early 1913. It transported to and from these remote islands scientists and government agents sent to obtain information take further steps to conserve birdlife on the Bird Reservation islands. In March, Thetis retrieved the scientists and agents and delivered them to Honolulu. That summer, Thetis made another Alaskan cruise before returning to the Honolulu Station on September 17th.

Thetis made several cruises to Lisianski, Necker, and Bird islands and French Frigate Shoals in early 1913. It transported to and from these remote islands scientists and government agents sent to obtain information take further steps to conserve birdlife on the Bird Reservation islands. In March, Thetis retrieved the scientists and agents and delivered them to Honolulu. That summer, Thetis made another Alaskan cruise before returning to the Honolulu Station on September 17th.

In December, after returning to the Honolulu station, Thetis received orders to cruise the Bird Islands in early 1916. In January, the cutter departed Honolulu on its last patrol of the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation. The weather was stormy and, as usual, landings on some of the islands were difficult. However, the crew found no evidence of poaching.

In February 1916, after completing its mission to Midway and other bird islands, Thetis returned to Honolulu. In March, the cutter set sail for the West Coast and, the next month, arrived in San Francisco where it was decommissioned. In June, a Canadian firm bought the cutter for its original purpose of hunting fur seals in the Arctic. Thetis’s 79-year lifespan ended aground on a beach near St. John’s, Newfoundland in 1960.

Thetis served for nearly 20 years in the Pacific. During its career in Hawaiian waters, the ship recorded several accomplishments. It established the service’s Honolulu Station, which evolved into today’s Coast Guard District Fourteen. While on station, Thetis performed all the usual service missions in Hawaiian waters. Most importantly, Thetis patrolled Teddy Roosevelt’s Hawaiian Bird Reservation, ensuring the survival of numerous species of wild seabirds. Today, over 100 years after Thetis was tasked with preventing illegal poaching of seabirds, the Coast Guard continues to monitor and interdict illegal catches and harvesting of wild species in the Pacific Basin.