On 4 December 1938, in response to Mussolini’s clams: ”Corsica, Savoia, Tunisia a noi!”, thousands of Corsicans took an oath in front of the war memorial in Bastia, ”Before the world, with all our souls, on our glories, on our tombs, on our cradles, we swear to live and die French”.

North Africa (operation Torch). Hitler invaded the Free Zone of France (operation Attila). 80,000 Italians occupied Corsica on 11 November and, in June 1943, were joined by 14,000 Germans of the SS Reichsführer brigade, for nearly one occupant for every two inhabitants – the island has approximately 200,000 inhabitants. A decisive change occurred in the Mediterranean in November 1942. Germany no doubt did not have any territorial ambitions over the islands of the western Mediterranean; but starting in November, Corsica, Sicily and Sardinia became strategic outposts to be defended. Furthermore, Germany feared that the population of Corsica was hoping for and would help with a possible Anglo-American landing.

In December 1942, General Giraud, co-President of the Comité Français de Libération Nationale (French Committee of National Liberation) with General de Gaulle, sent the Pearl Harbor mission to Corsica on the submarine Casabianca to set up Résistance networks.

Fred Scamaroni. Source : Musée de l’Odre de la Libération

Fred Scamaroni, who created the Gaullist network Action R2 Corse in 1941, was sent by General de Gaulle in January 1943 to try and unify the Résistance. Despite an encouraging start, this was not to be, as Scamaroni was arrested by OVRA (the Italian political police), tortured, and committed suicide in Ajaccio on 19 March 1943 to ensure he wouldn’t talk. His network was then dismantled.

On 4 April 1943, General Giraud sent Paul Colonna d’Istria to try to ”unite all the elements of the Résistance […], to look for paradrop sites, to define military objectives for simultaneous attacks on ”D” day that would paralyse defences and allow the landing of an expeditionary corps that the commander-in-chief’s headquarters were secretly preparing in Algiers”. Its activities made a decisive contribution in leading the resistant fighters to the final victory alongside the French Army.

In the meantime, the submarine Casabianca brought agents, arms and munitions to arm the island’s Résistance. This submarine had escaped the sinking of the fleet at Toulon and was to become a strong symbol of the connections between Algiers, the Résistance and the French Army.

During the month of June, OVRA arrested many patriots. Some were executed (Pierre Griffi, Jean Nicoli, Michel Bozzi), while others were deported to Italy.

On 10 July 1943, the Allies landed in Sicily (operation Husky). Mussolini was deposed. In August 1943, the breakdown of the Axis forces’ military situation in Italy led the Germans to envisage a new strategy. The German plan called for abandoning Sardinia and concentrating the German troops in Corsica and on Elba to protect their positions in Northern and Central Italy. The SS brigade was reinforced, while the 90th Panzergrenadier division prepared to leave Sardinia for Corsica.

On 3 September, Italy secretly signed an armistice with the Allies. It was promulgated on the 8th and stated that Corsica should be ”returned to the Allies” (sic). On the 9th, the Allies landed in Salerno, south of Naples.

The struggle for liberation

A – The Italian armistice of 8 September: the uprising in Corsica and new German-Italian relations

On 4 September, a radio message alerted the Corsican Résistance of an imminent landing.

Corsican resistance fighters examining German weapons (an MG 34 machine gun and its magazine, a Mauser 98 rifle) taken during the military operations to liberate the island. Source: ECPAD

During the evening of the 8th, General Magli received two ultimatums: one from the German command demanding that the Italian forces be disarmed, the other from Paul Colonna d’Istria calling for an unambiguous position for or against the Corsican Résistance. The first was rejected; the second was accepted with some reluctance, which explains why the Italian troops did not truly engage against the Germans until two weeks later. The situation was very confused. General Magli’s positive response to Colonna d’Istria was not the final word; not everyone in the Italian Army recognised the authority of the head of the Italian government, Marshal Badoglio.

Tensions with the Germans grew: in the early hours of the next day, serious incidents broke out in the port of Bastia. The Italian air defences shot at German aircraft, and an Italian ship setting sail was attacked and burned by the Germans. At dawn on 9 September, several German ships were damaged by the Italian artillery batteries and the prisoners were placed under the control of the Italian military authorities. That same day, in the city, Italian soldiers and patriots took the citadel, the train station and the main roads; the premises of the Légion des Combattants (Legion of Résistance Fighters) became the headquarters for the National Front resistance fighters.

Other cases of immediate cooperation between the Italians and the Corsican resistance fighters were reported (at Sartène, for example).

The Ajaccio uprising, 9 September 1943. Source: Service Historique de la Défense

Ajaccio rose up on 9 September. The Germans stationed at Parata were stopped at the entry to the city on 10 September by a group of resistance fighters. They withdrew by sea, as they were outnumbered and any attempt at using the roads a risky proposition. Thus, the port of Ajaccio remained free and available for the armies to land.

On 12 September, Hitler changed the army staff’s plan and ordered the evacuation of the two big islands, Sardinia and Corsica, but not without a transitional period to allow the German forces to regroup and for stocks to be evacuated. This plan entailed taking back control of Corsica’s roads.

This demonstrated a poor understanding of the island’s geography and the force ratio. General von Senger did attempt to push through toward the west side of the island, but he quickly realised how determined the partisans were and refused to get bogged down in deadly, uncertain guerrilla warfare.

Starting on 17 September, he concentrated his action on the east coast road network and the port of Bastia to evacuate the units under his command: along with the Reichsführer brigade, he had to get the 90th Panzer division through, which had arrived from Sardinia, i.e. some 32,000 men with heavy equipment (tanks, artillery guns, materiel and various vehicles); a battalion of Italian paratroopers followed the Germans in their retreat. They all had to fight in Italy after leaving Corsica.

B – Help from Algiers after the uprising of 9 September

The uprising ordered by the National Front, during which all the resistance movements came together thanks to the actions of Paul Colonna d’Istria, was not a rash action. It was the result of a logical examination of the situation: for the most part, no doubt, the Italians were ready to capitulate, but in many areas around Europe and Africa, when the Italians had abandoned their positions, fast, brutal interventions were undertaken by the Germans. In Corsica, they risked having a Germans stranglehold on the island if they waited too long. The patriots were convinced that they were going to be up against a disciplined, well-trained enemy.

On 8 September in Algiers, Giovoni (a National Front leader) met with General Giraud who promised him assistance, without informing General de Gaulle. That very evening, the insurrection began on the island, taking the authorities in Algiers off guard.

General Giraud, aware of the danger facing the resistant fighters, took a decision that was ”daring and risky” according to General de Gaulle, to send General Henri Martin’s 1st Army Corps to help the Résistance.

But the logistical problems were enormous. The allied command was unable to change its general strategy by launching a long-distance amphibious operation in Corsica with part of the resources planned for Salerno.

At least the French could use two submarines: the Casabianca and the Aréthuse, as well as two destroyers and two torpedo boats. The port of Ajaccio was free, as was the Campo dell’Oro, which was hit by a German air attack on 12 September, but where an allied pursuit aviation squadron was able to land.

The first to land were the men of the 1st shock battalion created by General Giraud in April 1943. They made the crossing packed into the Casabianca. Placed under the orders of Commander Gambiez, they were particularly well trained in the kind of combat that awaited them on the island. From 14 to 17 September, they waited for their marching orders and were joined in Ajaccio by the 1st Moroccan Tirailleur regiment, by spahis and goumiers, as well as by artillery and engineering elements; in all, 6,000 men, 400 tonnes of arms, jeeps, antiaircraft guns, fuel and food were unloaded in ten days. Ajaccio thus played the role of a bridgehead. The troops who came from Algeria provided support to the patriots who had begun to defend the passages between the two sides of the island by themselves.

The 1st shock battalion, formed in Algiers, was the first unit to set foot on French soil, at Ajaccio, on 13 and 14 September 1943. Source: ECPAD France

It was already impossible for the Germans to imagine the total occupation of Corsica (at least without reinforcements). On 11 September, the Italian authorities received an order to treat the Germans as enemies.

General Henri Martin contacted General Magli upon his arrival on 17 September. In charge of coordinating the troops who had landed, he wanted to define the terms and conditions for Franco-Italian cooperation. An agreement was finally reached on 21 September, calling for joint action in the south of the island and a converging attack on Bastia: the ”Cremona” division was to take part in the battles of Porto Vecchio, Sotta and Bonifacio on 23 and 24 September and the ”Friuli” division in the battles of the Teghime Pass battles at the end of the same month.

On 21 September, General Giraud in turn came to oversee the operations on the ground and to meet General Magli; the Italians were officially fighting alongside the French forces and provided them with important support.

The intervention called Operation ”Vésuve”, hastily decided upon in Algiers, was well under way and such disparate elements as the Corsican partisans, troops from the Army of Africa and Italian troops were able to cooperate in a satisfactory manner, which was amazing given the circumstances.

C – Corsican patriots in the liberation struggle

Corsican patriots fighting in the maquis. Source: Service Historique de la Défense

The period of fighting did not have the same effect everywhere:

– Ajaccio, the prefecture of Corsica, was completely liberated on 9 September. The population watched as troops landed and freely expressed their joy. The day before, the offices of the Milice, the Parti Populaire Français (French Popular Party) and collaborationist newspapers had been taken over and ransacked. Le Patriote (the National Front newspaper), published clandestinely, appeared on the presses of La Jeune Corse. People sang La Marseillaise in the streets.

– In Sartène, the popular uprising was met with a German intervention targeting the population on Place Porta.

– In Bastia, there was fighting between the Italians and the Germans in the city and on the port. On 14 September, the Germans, who had taken control of the situation, threatened the city with destruction and only allowed the population to go out between 11 and 12 in the morning. The patriots, thinking their city had been liberated, occupied the city hall and the sub-prefecture, and had to go underground after an intervention by a German column from Casamozza and a Stuka attack.

– In Ajaccio, where the conditions were better, administrative changes were quickly made: the representatives of the Vichy government surrendered their power without resistance.

On 9 September, a new municipal government headed by E. Macchini was set up and the National Front set up a ”Prefecture Council” alongside the Prefect; Mr Pelletier, who stepped aside. This council took the first measures dissolving the collaborationist movements and political parties. Instructions were sent to all the National Front arrondissement committees with plans to take control of town halls – and to undertake the first purges.

Unequally armed and often inexperienced, there were more than 10,000 of them September, and most of them had not received any serious military preparation. The patriots fought without assistance for the first eight to ten days. During this period, the Germans still sought to open up a passage toward the west in the regions of L’Ospedale, Ghisoni, Barchetta and Folelli. To the south, the SS Reichsführer brigade holed up in Sartène was a force to reckon with.

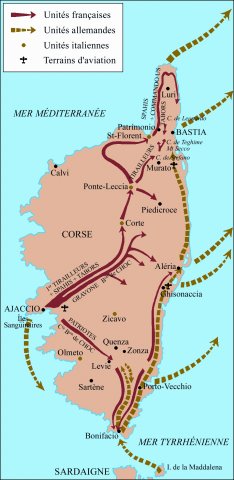

Military operations map. Source: SGA/DMPA

Cliquez sur la carte pour l’agrandir

The Germans wanted to save their materiel and fuel depots, such as the one in Quenza which was attacked by the National Front and Commander Pietri’s men on 15 September; by ensuring control of the road system, the resistance fighters kept the German troops from Porto Vecchio from joining up with those from Quenza and Sartène. Movement through the region around Levie was blocked. On the 17th, a shock battalion company was decisive in backing up the Résistance – despite an intervention by their aviation, the Germans were defeated. General von Senger, well aware of the high price that would have to be paid for any action toward the west, spent the next period evacuating his forces to Bastia. The second phase of fighting had begun – on the 18th, on the road from Bonifacio to Porto Vecchio, and then on the 22nd in the area of Conca, the hills overlooking the road were used a base for launching attacks. But the 90th German division was an armoured division, it could sustain losses, it could be slowed down, but it could not be stopped.

Maquisard groups were called into combat as the Germans slowly moved north. Those in Vezzani and Prunelli di Fiumorbo went into action on 23 and 24 September. The Germans lost control of the airfields at Ghisonaccia and Borgo,which they used for their evacuation and for aerial support operations. At the end of September, fighting raged at Casinca. The shock battalion found guides amongst the patriots who were indispensable as no military maps of the region were available. Furthermore, a 4th company was formed, made up of volunteers recruited on site. The population fed and informed the fighters, but the wounded suffered from a lack of care: no medical services had followed the troops into this zone.

During the military operations for the liberation of Corsica, the French Army launched an attack on the port of Bastia on 30 September 1943 to keep the Germans from landing. The goumiers of the 2nd GTM (Groupe de Tabors Marocains – Moroccan Tabor Group) took part in taking the city and finally entered it on 2 October. Source: ECPAD

At the end of September and during the first three days of October, the German sought only to protect their retreat to the port of Bastia. Their artillery slowed down access. The patriots and the ”shocks” came up from the south while the tabors, spahis and Italian troops moved in from the west with the resistance fighters from the Corte region and La Balagne. The Moroccans played a decisive role in the fighting – San Stefano Pass was taken on 30 September and Teghime Pass on 3 October. The shock battalion took control of Cap Corse, although not without skirmishes with the Germans at Pietracorbara. Bastia was liberated on October 4, but was devastated by the fighting and American bombings.

Goumiers and Italian soldiers, September 1943. Source: ECPAD

The 90th Panzergrenadier division left the island, weakened by the destruction of some 100 tanks, 600 artillery guns and 5,000 miscellaneous vehicles. Marshal Kesselring himself recognised that he could not stop General Clark’s landing at Salerno. Some patriots were killed in the fighting alongside the French and Italian soldiers, while others, caught armed by the Germans, were immediately shot – there were at least 25 summary executions. In all, it is estimated that the fighting left the following number of victims: the German troops lost approximately 1,600 men, including 1,000 killed and 400 prisoners; the Italians had 637 killed and 557 wounded; on the French side, the Résistance recorded 170 dead and approximately 300 wounded; the regular troops recorded 75 dead (including Officer Cadet Michelin, the first French officer to fall on national territory) and 239 wounded. There were considerable material damages on the combat sites: many bridges were blown up, houses were destroyed and Bastia was bombed by the allies five times between 13 September and 4 October, not to mention the artillery fire.

Bombing of Bastia, October 1943. Source: Service Historique de la Défense

The neighbourhoods of the port, the train station, and even the cemetery were destroyed, and the east coast railroad was out of service.

During his visit to Corsica from 8 to 10 October, General de Gaulle praised the efforts and sacrifices made. His speeches were indicative of his heartfelt emotion. The Corsican people acclaimed the co-President of the Comité Français de Libération Nationale (French Committee of National Liberation). The island, cut off from continental France, now depended on Algiers. For its inhabitants, the Liberation did not mean peace, but rather a return to war alongside the Allies. In this way, the situation in this French department was unique: during the year 1944, 12,000 Corsicans between the ages of 20 and 28 were mobilised. Furthermore, the region was used as a naval air base to control maritime connections, as a base for attacks against Central and Northern Italy, which were still held by the Germans, and, in August 1944, as the home base for the landing in Provence.

The French flag raised by Captain Thene, commander of the 73rd Goum battalion, flying over Bastia City Hall, liberated by French troops on 2 October 1943 (tirailleurs, goumiers and a shock battalion). Source: ECPAD

On 6 June 1944, the Allies landed in Normandy. After Corsica, Calvados became the second French department to be liberated. The FFI in Caen took the name of Fred Scamaroni, hero and martyr of the Corsican Résistance. On 8 July 1944, the men of the Scamaroni Company raised the French flag before the Abbaye aux Hommes in Caen. Corsica holds an important place in the history of the Résistance and the Liberation. It was the first piece of French territory to be liberated by its inhabitants and by French soldiers, without any intervention by the Anglo-American forces. Its fighters and strategic space provided to the Allies by the Corsican Résistance arrived just in time, at a decisive moment for the war in the Mediterranean, contributing to the Nazi’s setbacks in Italy and southern France.

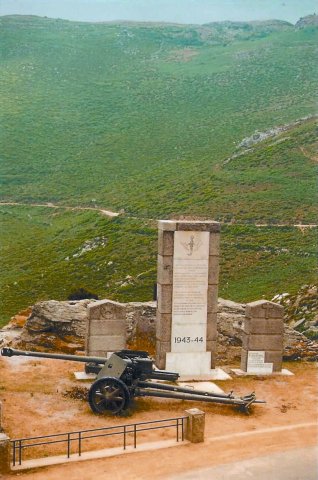

Monument dedicated to the soldiers of the 2nd GTM, Barbaggio, Teghime Pass. Source: Photo JF. Paccosi