By Georgy Tomin

No self-respecting old building is without its ghosts. The main academic building of the SVVMIU was old (built in 1913) and undoubtedly self-respecting—its position as the longest building in Europe obliged! And by the time the author arrived, it had already acquired its own ghost—the “ghost of Lieutenant Shostak.” Cadets who stood nightly fire watch in the building (a tireless duty) claimed that around midnight, an officer in white uniform No. 1 and with a burnt face would stomp loudly along the long parquet corridors—a graduate of the “Gollandiya,” Lieutenant Alexander Shostak, who died on the submarine K-278 “Komsomolets.”

Lieutenant Alexander Shostak

The longest building in Europe, however!

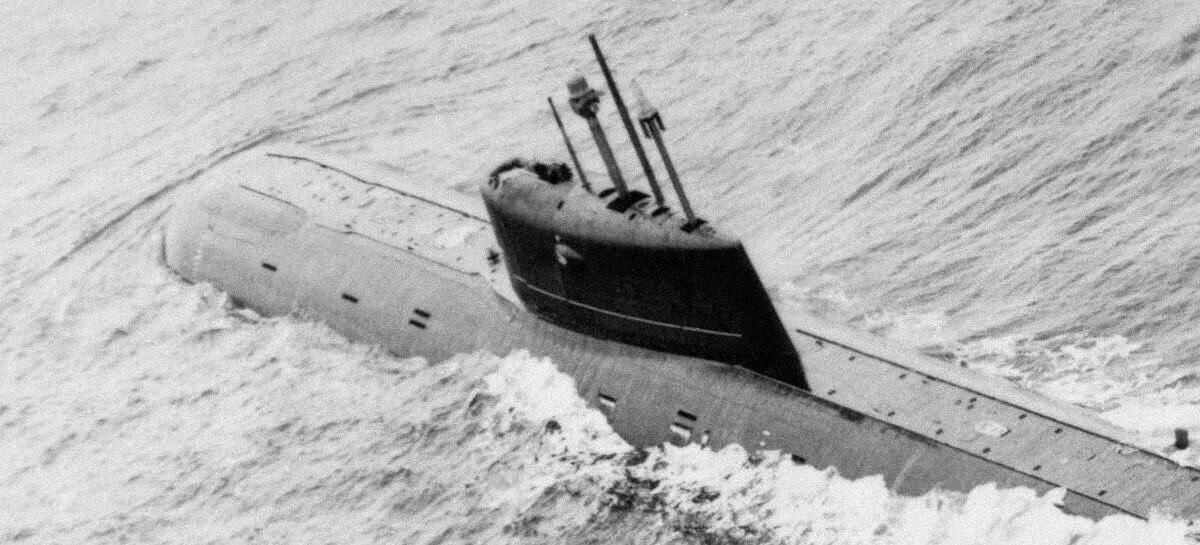

The K-278 was no ordinary submarine. The USSR struggled to maintain submarine parity with NATO countries, so it decided to make a quantum leap—to build a combat submarine capable of operating at depths accessible only to bathyscaphes. This offered several advantages: at such depths, no torpedo could reach the submarine—it would simply be crushed by the water pressure. Furthermore, depth charges lacked a moderator capable of sinking a target at depths greater than a kilometer.

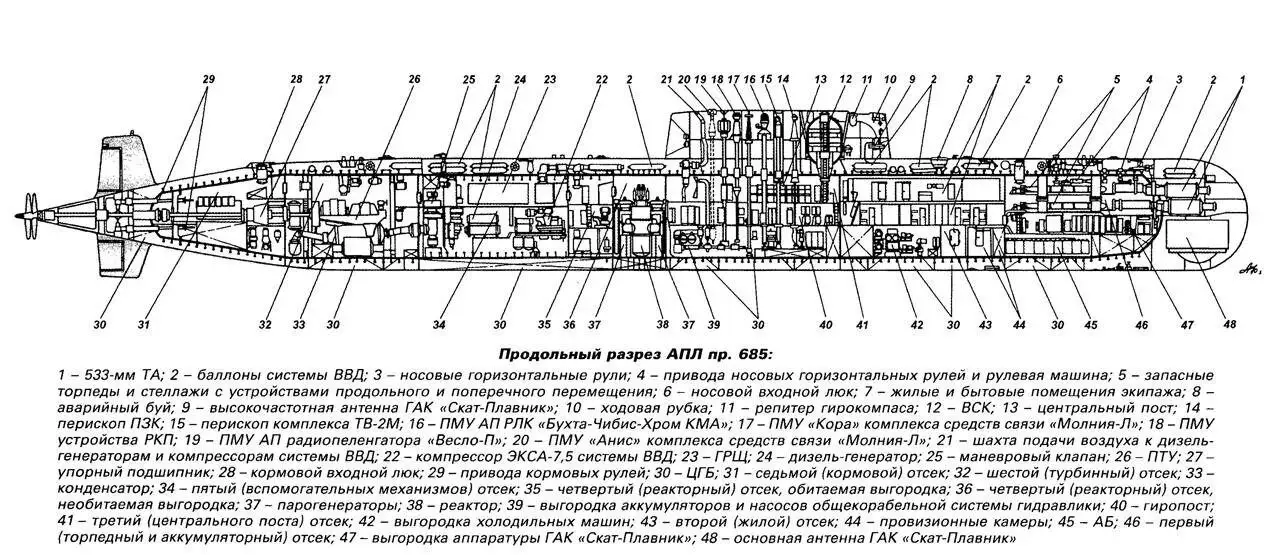

Research design work began in 1964 under the supervision of Nikolai Klimov, chief designer of the Rubin Central Design Bureau for Marine Engineering. The preliminary design was approved in July 1969, and in 1972, the technical design for the deep-sea submarine was approved by the Navy and the Ministry of Shipbuilding Industry. However, Nikolai Klimov himself died in 1976, two years before the ship’s keel was laid. The performance characteristics of the new submarine, designated Project 685 Plavnik, were as follows: length 117.5 meters, width 10.7 meters, surface draft 8 meters, surface displacement 5,880 tons, submerged displacement 8,500 tons, and crew of 57 (later increased to 64). Armament: six 533 mm torpedo tubes with 16 spare torpedoes on racks.

K-278 in section

Even the small crew of the submarine suggests that the boat was a highly innovative one for the Soviet Navy, boasting extensive automation. But its main feature was its ability to operate at depths of up to 1,000 meters. More precisely, 1,000 meters was the operational depth. Furthermore, the submarine had a single reactor, a rarity for Soviet submarines. The turbine powered it produced 43,000 horsepower. The turbine drove two independent turbogenerators, and a backup diesel generator was also on board.

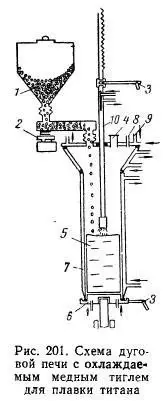

Arc furnace for melting titanium

The K-278 submarine’s high diving depth was achieved by using a lightweight titanium alloy as the structural material for its pressure hull, which led naval wits to dub the submarine the “goldfish.” Titanium, while cheaper than gold on the international market at the time, was only slightly cheaper—two to three times (in 2025, a gram of titanium costs around 8 rubles; in the 1970s, it was orders of magnitude more expensive!). The fact is that in 1956, the USSR developed the “vacuum arc with a consumable electrode” method of smelting titanium. As a result, by 1990, the USSR was smelting 1.9 times more titanium than the rest of the world combined, and four times more than the United States. Titanium is roughly equal in strength to steel, but is 40 percent lighter, making it possible to build thicker pressure hulls for submarines.

Project 705 “Goldfish”

The first “goldfish” were the Project 705 Lira submarines, the last of which was decommissioned in 1989. The use of titanium pressure hulls in submarine construction allowed a number of Soviet submarines with titanium hulls to achieve record-breaking results. For example, the Project 661 submarine K-162 holds a still-unbroken underwater speed record of 44.7 knots! In short, Soviet shipbuilders had experience working with titanium by the time construction of the K-278 began.

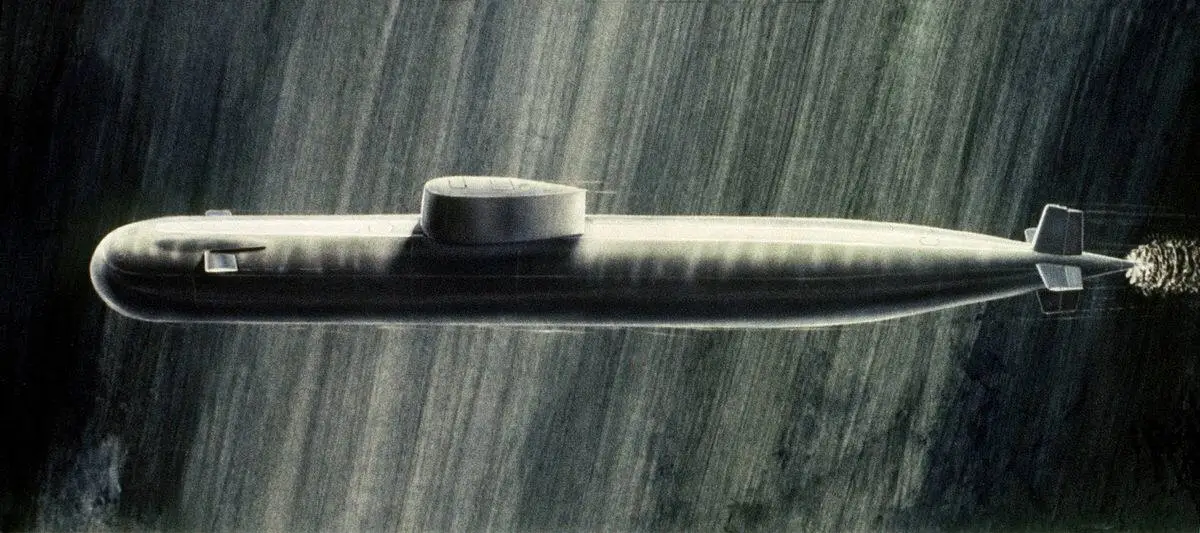

K-278 underwater

The pressure hull of the K-278 submarine was divided into seven compartments: 1 — torpedo compartment, 2 — living quarters, 3 — main power plant, 4 — reactor compartment, 5 — electrical engineering compartment, 6 — turbine compartment, and 7 — auxiliary machinery compartment. To ensure the submarine’s survivability, VPL (air-foam boat) foam generators were installed in compartments 1 and 7, and LOH (submarine volumetric chemical) fire extinguishing systems were installed in each compartment except the reactor compartment. LOH could be supplied to a compartment from either its own or an adjacent compartment. Two high-power centrifugal pumps were used to pump water out of the compartments.

In an emergency, the main ballast tank could be purged using powder gas generators. Compartments 1, 3, and 7 had hatches through which the crew could abandon ship (or, well, enter it). Above the entrance hatch of Compartment 3 was a floating capsule (VSK), which allowed the entire crew to exit the sunken submarine at once. The capsule contained emergency food, water, a radio, and signaling equipment, while its hull housed inflatable rafts for 20 people each.

In short, the submarine’s weakest link was the crew: the functioning of all this machinery depended on their training. And therein lay the problem. The fact is that the K-278 nuclear submarine was extremely complex and required an extremely high level of training from each individual submariner and teamwork as a whole. And to its credit, such a crew was indeed present on the nuclear submarine! The fact is that on the lead hulls of large series submarines or on experimental submarines, the crew is always better trained than the average. And the K-278 was precisely that—the first and only deep-diving submarine of its kind.

The crew accepted the submarine from the industry at 70–80 percent completion, when they had access to systems and mechanisms that would be inaccessible when fully operational. And when the shipyard’s specialists could advise the submariners on what was going on. Before being cleared for use, each crew member took a test, and an uncertain answer to any question automatically sent the examinee to a retake.

Officers, warrant officers, and petty officers of the K-278 crew, with Captain 1st Rank Yuri Zelensky sitting in the center.

The K-278’s crew was formed in 1981. The submarine’s first commander was Captain 1st Rank Yuriy Zelensky, who had experience commanding a newly built submarine. The crew completed a full training course at the training center, then participated in the submarine’s completion, acceptance trials, and state trials. Overall, the crew’s level of training was… Higher than anything else! But, as I’ve written before, a submarine typically has two crews. Regarding the K-278, the question lingered for a long time: should a full-fledged second crew be trained for the submarine, or should they limit themselves to a “technical” crew, servicing the submarine at base? Ultimately, the decision was made to train a second crew. However, by that time, the submarine had already been completed, passed state trials, and arrived at base. Therefore, its training was… much more theoretical: it did not participate in the ship’s completion.

A deep-sea submarine in its natural habitat

In 1984, the Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Navy approved the State Commission’s acceptance certificate, and K-278 was commissioned into the Navy. By the end of 1985, Captain 1st Rank Zelensky’s crew had successfully completed all course assignments—the submarine “entered the campaign,” and the crew began receiving “naval” assignments. On August 4, the newborn submarine made a record-breaking dive—first to 1,000 meters, then another 27 to test its response to a possible submergence. The submarine performed admirably—several titanium bolts were sheared off by the intense pressure applied to the hull, several leaks were noted at flange joints, minor defects were noted in the stern tube seal, the lower hatch cover, and… that’s it! K-278 proved that the shipbuilders had mastered the task, and the Soviet Navy acquired the world’s only deep-diving nuclear submarine.

Northern Fleet Commander-in-Chief Admiral Ivan Kapitanets

Upon returning to base, the submarine was inspected by Northern Fleet Commander-in-Chief I. M. Kapitanets, who congratulated the crew on their dive and called them “a crew of heroes.” These last words weren’t mere rhetoric—all crew members were nominated for state awards. However, the award lists were rejected by the fleet’s political directorate. Why? They didn’t include a single naval “political worker,” except for the submarine’s political officer, Vasily Kondryukov, who had actually participated in the deep-sea dive.

In 1986, K-278 conducted experimental tactical exercises in the Norwegian Sea as command determined how best to utilize the trump card they had acquired. The exercises included a test of the VSK surface from its operational depth, and the submarine conducted its first fully autonomous voyage. The submarine’s trial period had ended. The commission concluded that the creation of a deep-sea combat submarine was a major scientific and technological achievement for Russian shipbuilding. The submarine was planned to be used to develop deep-sea navigation tactics as part of a research program. However, since the ship was unique, it was recommended to limit its use to the extent necessary to maintain the high qualifications of the crew.

Captain 1st Rank Evgeny Vanin

Zelensky’s crew completed another combat mission; no emergencies occurred, and all assigned tasks were completed in full. In October 1988, K-278 received its proper name, “Komsomolets,” for its successes. Planning for further research began; Komsomolets was scheduled to sail on its next mission alongside the research vessel “Akademik A.N. Krylov,” but… Suddenly, the decision was made to send the submarine on a routine mission, with a second crew under Captain 1st Rank Yevgeny Vanin.

The second crew was considered front-line, but its level of training was significantly lower than the first: the training center lacked simulators for the new submarine. The crew first saw the submarine in 1985, when it was already at sea for trial operations. In principle, there was nothing wrong with this: the crew simply needed time to learn the ship and practice all the required standards. But the trial program was in shambles, and the submarine wasn’t handed over to the second crew until its completion. Essentially, the crew was a “technical” one—capable of keeping the Komsomolets at base (only a few crew members had ever sailed on the K-278). However, the crew performed well in this task, completing a second course of training at the training center in 1986 and, in early 1987, receiving the opportunity to practice Task L-1 (“Preparing a Submarine for Sea”). The second crew logged 32 days at sea.

Komsomolets at sea

In 1988, Komsomolets again set out on an independent cruise with the first crew. The second crew was sent to a training center for a third time. By the time they set out, the second crew had been off-duty for over six months. According to the VMF-75 submarine safety regulations, in this case, the crew must be given 30-50 days (including completing tasks L-1 and L-2) to rehabilitate lost skills. However, the crew was not granted this time: a day for a control check for task L-1, and a three-day pre-repair voyage, combined with completing task L-2 (according to the documents, this requires at least five days). The remaining time was spent on inter-voyage repairs. In 1988, the crew spent only 24 days at sea.

The senior officer on board was Captain 1st Rank Boris Kolyada.

On February 11, 1989, Komsomolets and its second crew set out to sea for a final readiness check for combat duty. Throughout the entire check, elevated oxygen levels were recorded in the atmosphere of compartment 7, at times exceeding 30 percent. On February 28, 1989, the submarine and its second crew were prepared for patrol duty. First Mate O. G. Avanesov, BC-5 Division Commanders V. A. Yudin and A. M. Ispenkov, and Hydroacoustic Engineer I. V. Kalinin were seconded from the first crew. Captain 1st Rank Vanin and several officers had experience with first-crew deployments.

The ship’s deputy commander for political affairs arrived on board two weeks before the deployment. Eight lieutenants had experience sailing for up to 35 days at sea. Most of the midshipmen had up to 70 days of experience at sea, but some were not authorized to perform their duties independently, and Warrant Officer Yu. P. Podgornov (a hold technician!) had never served on a submarine before. Of the 15 sailors and petty officers serving on active duty, eight were subject to discharge after the cruise, and two were drafted into the navy in 1988. The senior officer on board was the deputy division commander, Captain 1st Rank B. G. Kolyada, who had previously commanded Project 705 submarines but had not completed retraining on the K-278. On February 28, the Komsomolets set sail with 69 sailors, petty officers, midshipmen, and officers on board. Captain 1st Rank Vanin’s crew was scheduled for a 90-day voyage.

Komsomolets at sea

April 7, day 38 of the expedition. The submarine is traveling at a depth of 387 meters, traveling at 8 knots, and is on combat alert #2, with the second shift on watch. The propulsion plant is operating without issue, the atmospheric gas composition is normal, and all equipment is in good working order, with the exception of the television system monitoring the compartments and the oxygen sensors in compartments 5 and 7. At 11:06, a sharp ringing breaks the silence, and the ship’s intercom announces, “Emergency alarm! Fire in compartment 7! Ascend to a depth of 50 meters!”

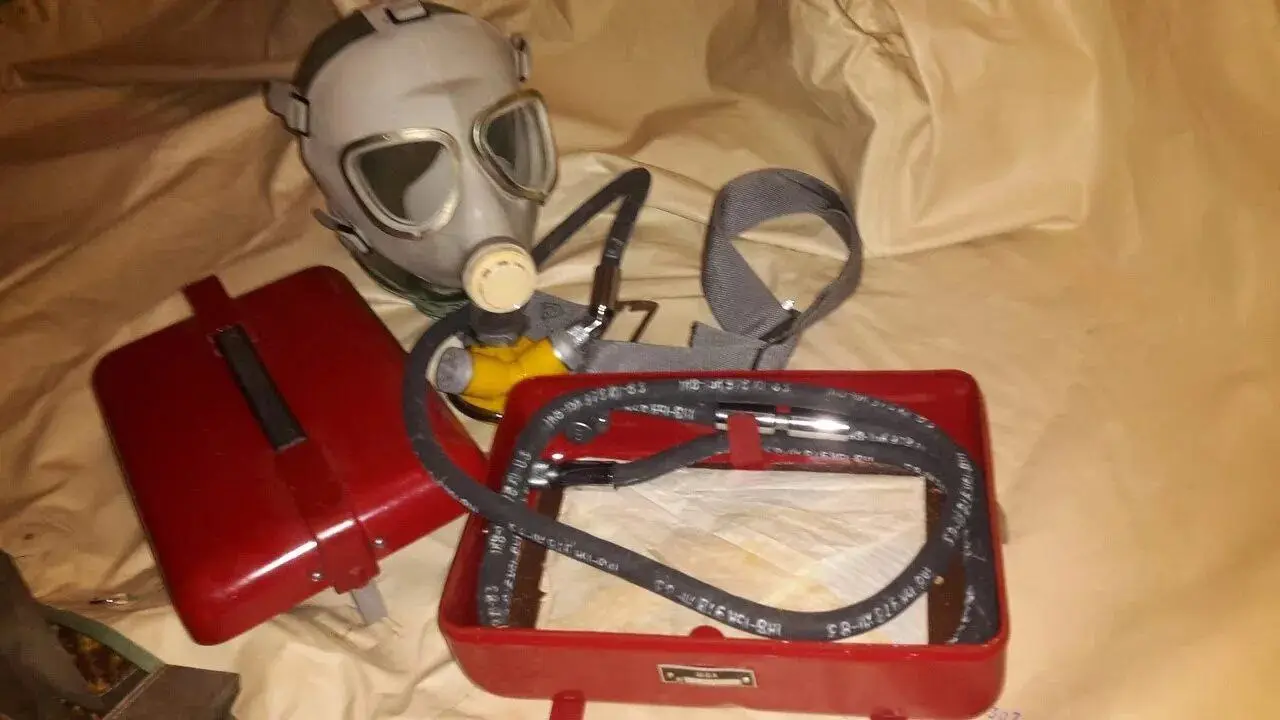

LOH is not at all what you think!

At 11:03, the watchman reported to the Central Station: “The temperature in Compartment 7 is over 70 degrees Celsius, and the insulation resistance of the compartment’s power grid is low.” The watchman in Compartment 7 failed to respond to the order to initiate a fire alarm in the compartment. The watchmen in Compartments 5 and 6 were ordered to initiate a fire alarm in Compartment 7, but they were also unable to contact them. The commander of the electromechanical warfare unit, Captain 2nd Rank Valentin Babenko, assumed command of the damage control operation. The watchman was replaced by the first mate, Captain 2nd Rank Oleg Avanesov, and the assistant commander transferred to the emergency communications station with the ship’s compartments. Deputy Division Commander Captain 1st Rank Kolyada arrived at the Main Control Station to find everyone in position.

Warrant Officer Vladimir Kolotilin, remote control group technician

At this time, Warrant Officer Kolotilin reported smoke coming from Compartment 6 in Compartment 7. He received the order to send a smoke detector to Compartment 7 from Compartment 6. At 11:10, Compartment 6 reported that the smoke leaks had been eliminated, but the compartment was difficult to breathe. At 11:16, Warrant Officer Kolotilin reported turbine oil coming into the compartment from under the turbogenerator. In this situation, the television cameras in Compartments 6 and 7 would have been very useful, but the television monitoring system was not working (the quality of Soviet cameras was so-so; I never saw the compartment cameras working…).

The submarine was surfacing at 10 knots when the main turbine stopped—the turbine protection system (the surfacing “under the turbine protection system” prevented the bulkhead between Compartments 6 and 7 from being sealed—the propeller shaft was rotating) was triggered. At 11:14, the central group of the central control room was purged, and at 11:16, the Komsomolets surfaced completely, having purged its ballast. At 11:20, the upper conning tower hatch was opened, and Captain 1st Rank Kolyada and the submarine’s assistant commander, Lieutenant Commander A. Verezgov, emerged onto the bridge. Communication between the bridge and the main control room was lost, but was later restored.

Why did the fire start? Compartment 7 contained a large amount of electrical equipment, which tends to spark occasionally. Under normal conditions, this isn’t a problem, but with elevated oxygen levels… The lower aft section of the compartment contained turbine oil, paint, and electrical cable. If the turbine oil had ignited under normal oxygen levels, the oxygen in the compartment would have quickly burned off, and the fire would have extinguished itself. But with elevated oxygen levels, as calculations later showed, the temperature could exceed 500 degrees Celsius, and the high-pressure air system fittings could heat up to 220 degrees Celsius, at which point the synthetic gaskets lose their properties and air begins to flow into the compartment, fueling combustion. Under these conditions, everything starts to burn! But most importantly, elevated oxygen levels in a compartment can completely neutralize the effects of the freon in the LOH system.

It is known that the oxygen sensor in the 7th compartment was malfunctioning; in October 1988, it even had to be repaired. The head of the Komsomolets chemical service, Lieutenant Commander Gregulev (whom G.T. did his diploma project with ) later reported: “…There was only one gas control—on the control panel. I couldn’t control the air throughout the entire submarine. In the stern, oxygen distribution was automatic.” Unfortunately, this is not uncommon on submarines. Excessive oxygen levels in a compartment often lead to fires: with 30 percent oxygen in the atmosphere, any spark can cause a full-scale fire. Or even spontaneous combustion of an oily rag can occur. The entry of high-pressure air into the compartment turned an ordinary fire into a blast furnace.

It’s worth noting right away that Vanin’s crew made several mistakes that a more experienced crew would have avoided. First, the emergency alarm was sounded three minutes after the fire in compartment 7 was detected. Three minutes is a very long time in a developing fire! Furthermore, the commanders of compartments 6 and 7 were detained at the main control center for a briefing, resulting in the bulkhead between compartments 6 and 7 not being sealed. Furthermore, the valves of the high-pressure air system supplying the aft compartment were not closed. All of these measures are mandatory in this situation, and with a more experienced crew, they would have been carried out.

The high-pressure air entering compartment 7 inflated the compartment, resulting in oil flowing through the unsealed oil lines into compartment 6, which Warrant Officer Kolotilin noticed. At 11:18, the fire spread to compartment 6. High-pressure air entering here triggered the reactor’s emergency protection system and shut down both turbogenerators. Compressors and fans lost power, and the compartment temperature began to rise, causing the valves of the fourth high-pressure air system to open. Between 11:16 and 12:00, air from three of the four high-pressure air systems—6.5 tons of air—was released into compartments 7 and 6! In compartments 7 and 6, the temperature reached 1,100 and 450 degrees Celsius, respectively. For comparison, the temperature in a blast furnace reaches 2,000 degrees Celsius—comparable values. And considering that the pressure in the compartments rose to 13 atmospheres… The

fire lasted an hour in compartment 7, and 30-35 minutes in compartment 6. This was enough to burn out the seals of the overboard valves and the insulation of the cables extending from the pressure hull. All of this was forced out by the excess pressure in the compartments, and water began to enter the pressure hull. According to experts’ estimates, 300-500 liters of water were entering the compartments per minute. Furthermore, the fire caused the hatch of the 7th compartment and the seals of the steering gear to become unsealed. Hot, pressurized combustion products from the depressurized pressure hull began to flow into Central City Hospital No. 10, causing a breach of its seal.

Around 12:00, the venting of high-pressure fuel into the compartments ceased, extinguishing the fire. Meanwhile, as the fire progressed, combustion products began to spread throughout the submarine. At 11:22, smoke coming from the rudder indicator unit forced everyone on the main control unit to put on personal protective equipment. This smoke masked the entry of toxic combustion products from the stern into the hold of the third compartment through the unsealed trim line. Between 11:30 and 11:50, a large-scale flash occurred on the upper deck of the fifth compartment. It did not cause a fire, but several people were severely burned, most severely, Captain Lieutenant Nikolai Volkov and Lieutenant Alexander Shostak. Most likely, the ignition was caused by products of incomplete combustion of turbine oil, which entered the compartment through unclosed valves on the return steam line and through the steam-air mixture exhaust line. The oil heated up near the red-hot bulkhead, and in the 5th compartment there was also an increased oxygen content, a random spark, and…

SHDA is a hose-type breathing apparatus. These red boxes are attached to the ceiling, you pull the handle, and a mask falls onto your head…

When Warrant Officer Kadantsev cleared the upper hatch of the VSK and climbed onto the bridge, he noticed steam rising from the stern of the submarine. Captain 1st Rank Kolyada recalled exactly the same thing, also mentioning a bubbling sound near the side of the submarine—a sign of high-pressure airborne gases entering the depressurized compartments. The entry of combustion products into compartments 5, 3, and 2 prompted the crew to activate their breathing apparatus (HPA). However, the lines carrying air from the aft cylinder groups were not closed, and the submariners who activated their HPA began inhaling high concentrations of carbon monoxide, causing them to lose consciousness.

Captain 3rd Rank Vyacheslav Yudin, commander of the survivability division

At 12:06, Captain 3rd Rank Vyacheslav Yudin and Lieutenant Anatoly Tretyakov were sent aft on reconnaissance. They discovered Lieutenant Andrei Makhota and Warrant Officer Mikhail Valyavin in the equipment enclosure of Compartment 6 and escorted them out. After a short rest, Makhota and Valyavin were sent by the ship’s commander to Compartment 5 to provide assistance to the personnel there. They discovered eight people in the compartment: six activated by the IDA-59, two by the ShDA. Those activated by the ShDA could not be rescued. The ship’s doctor was able to revive four submariners from Compartment 2, who had also activated the ShDA. Using the ShDA in the conditions of such a fire was also a mistake, one that the submarine’s first crew would likely have avoided.

The VSK surfaced from a depth of 1,000 meters…

By 1:30 PM, the pressure in the emergency compartments had equalized with atmospheric pressure, and seawater began to enter. At 1:00 PM, the sub had a stern tilt of 1 degree, at 4:00 PM, 3 degrees, and at 5:00 PM, 6.3 degrees, according to the sub’s logbook and confirmed by aerial photography. With each passing minute, the amount of water entering the aft compartments increased—the stern sank, and the pressure increased. As the stern sank, the bow rose, and air began to escape from the exposed vent valves of the forward ballast tanks, causing the Komsomolets to lose buoyancy.

At 4:40 PM, the order was given to prepare for evacuation, prepare the lifeboats, and launch life rafts. Only one raft was launched, and another was dropped from an Il-38 aircraft. Between 17:03 and 17:05, the submarine began rapidly listing by the stern. When the trim reached 50-60 degrees at 17:08, the submarine submerged with 25 percent of its high-pressure fuel remaining, and with its compressors and bilge pumps still operational. The diesel generator, which provided power, continued to operate until the last possible moment, under the supervision of Captain 3rd Rank Anatoly Ispenkov, commander of the BC-5 electrical division. The submarine’s commander, Captain 1st Rank Vanin, and four other sailors managed to climb into the raft and surface, but after surfacing, the pressure difference in the raft blew off the top hatch, throwing Warrant Officer Sergei Chernikov into the sea. Only Warrant Officer Viktor Slyusarenko managed to escape alive.

Submariners on an overturned life raft, photograph from Komsomolskaya Pravda

As sad as it is to write, the crew had the opportunity to save the submarine. The floating base “Aleksey Khlobystov” was on its way to assist the K-278, and naval aircraft were circling above the stricken submarine. By the time the “Aleksey Khlobystov” arrived at the scene at 6:20 PM, 16 submariners had already died of hypothermia, and one (Captain 3rd Rank Ispenkov) had sunk with the submarine. Thirty surviving sailors were rescued from the water, and the bodies of 16 of the dead were recovered. The submarine’s diesel generator and bilge pumps were still working, and there was a high-pressure air reserve, meaning it had everything it needed to maintain buoyancy for at least several hours. From 2:18 PM, radio communications with the shore command post were maintained via an aircraft relay.

Rescued by boat from the Alexey Khdobystov

The accident resulted in the deaths of 42 submariners, the vast majority of whom—30—died before help arrived: two during the damage control battle, two from carbon monoxide poisoning, three unable to abandon ship, two perished with the ship at their combat posts, and three died on the floating base “Alexey Khlobystov” from the effects of hypothermia. Twenty-seven crew members of the K-278 Komsomolets submarine survived. By a decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on May 12, 1989, all crew members of the submarine were awarded the Order of the Red Banner.

Rescued submariners in the hospital

The most interesting part began with the investigation into the submarine’s sinking. The Navy command put forward a theory about certain “design flaws” that led to the Komsomolets’s demise. This theory was immediately rejected by those involved in the submarine’s operation. The fact is that any submarine has design flaws, but most of them operate without problems alongside them: a nuclear submarine is too complex a machine to avoid flaws; the challenge is to ensure those flaws aren’t fatal.

The Komsomolets had no fatal flaws. The crew’s errors during the damage control operation were obvious, but… But pursuing this line of inquiry could have raised unpleasant questions, such as: “Who sent a submarine to sea with an insufficiently trained crew?” The situation in this case was very similar to the K-429 accident, where the number of personnel assigned to the submarine also prevented the crew from going to sea. But there’s another similarity between these two accidents. In the case of the K-429, the flotilla’s chief of staff was Rear Admiral Oleg Frolov. In the case of the K-278 accident, he was also the commander of the 1st Flotilla of the Northern Fleet. The strong-willed approach to personnel decisions in these two cases is remarkably similar.

There’s a famous saying by I. V. Stalin: “Personnel decide everything.” Regardless of one’s overall opinion of the quarter-century reign of the “best friend of Soviet athletes,” one cannot help but note his correctness in this regard. The “human factor” in man-made disasters often takes the form of personnel shortcomings—an inappropriately placed individual can be the straw that triggers a cascade of malfunctions that leads to disaster. And a submarine that had every reason to be considered the best in the Soviet Navy will sink…

Reprinted from topwar.ru